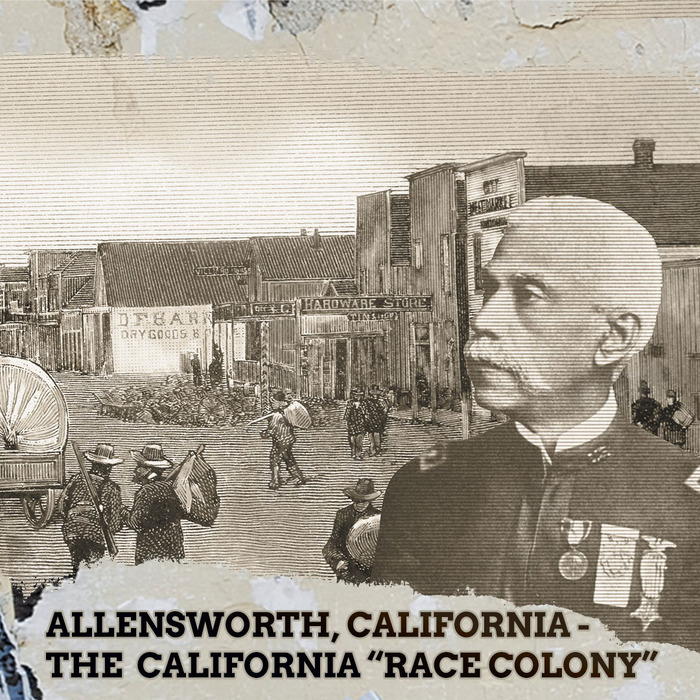

Source: creative services / iOne Digital

Almost 70 miles south of Fresno, California, tucked away in the small county of Tulare is a tiny state park. Although it may not look like much, it was once a true testament to Black American resilience.

MORE: The Black Town Under Lake Martin: A Father & Son’s Dream Of Greatness

How do you get a whole race of people to uplift themselves after years of persecution?

This was the very question Colonel Allen Allensworth asked himself before he embarked on one of the most important journeys in African American history–to build the first Black self-sufficient town in California.

Sadly, that journey would never get to live up to its full potential. Like so many other symbols of Black excellence in the early 1900s, Allensworth’s dream would be poisoned by racism’s venomous sting.

Colonel Allensworth was an American hero in every sense of the word and his story doesn’t get told nearly enough.

But this is Black Folklore, where we dive into America’s past to tell lesser-known Black stories that touch the soul. And yes, many of our stories end in tragedy, but that doesn’t make them any less inspiring.

There’s value in understanding what came before you.

Here is the amazing and tragic story of Allensworth, the only California town to be founded, financed, and governed by Black people.

Source: Fresno Bee / Getty

In 1842, Allen Allensworth was born a slave in Louisville, Kentucky, twenty years before the start of the Civil War.

The young boy would spend his entire childhood the property of a white slave owner.

Slaves in Kentucky were forbidden from education in fear of rebellion or uprising. In secret, Allensworth would master the English language, learning to read and write and cultivate a love for learning. But the only way he would truly be able to express this newfound love was to escape his bondage.

The first time Allen Allensworth tried to escape slavery he failed miserably. Although there is no record of his escape, there are a few bread crumbs from history we can follow to paint a picture.

In 1806, the Louisville Police department began to take shape in the form of five ‘watchmen’ appointed by the town’s trustees. In the south police forces, we created solely to preserve the system of slavery. It isn’t out of the question to believe that Allensworth was caught by the police and returned to his slave owner, who probably greeted him with a few lashings from the whip. But it wouldn’t deter Allensworth.

The start of the Civil War in 1861 would give him the opportunity he needed to run and never look back. He escaped slavery in 1862, seeking refuge behind Union lines. For the next several months, Allensworth would work as a civilian nurse for the 44th Illinois volunteer Infantry, until 1863 when become a seaman in the Union Navy serving on gunboats. When he left the Navy in 1865 with the rank of first-class petty officer, Allensworth leaned into the word of God and enrolled at Roger Williams University to study theology. While learning how to spread the gospel, he also met and married the love of his life, Josephine Leavell.

After becoming an ordained minister, Allensworth jumped right into the pulpit. He began giving serval sermons around his hometown of Louisville and became an instant success. The community began to look up to him and it propelled him into politics. In 1880 and 1884, Allensworth would represent Kentucky as one of their delegates to the Republic National convention.

Allensworth’s life had changed so much since his time in the Navy, but his heart was still with the soldiers. In 1882 he was tasked to help recruit Black chaplains for the all-Black military units. Instead of recruiting Black pastors, Allensworth took the position himself. He believed as a chaplain he could make the lives of the average Black soldier much better. For twenty years, Allensworth taught Black soldiers about spiritual health and educational well-being. He was only the second African American, after Henry Plummer, named to serve as a U.S. Army Chaplain. In 1906 he retired from the Army as the highest-ranked Black man in the U.S. Armed Forces.

Retirement didn’t slow Allensworth down one bit. After his second stint in the army, the former slave turned Colonel traveled the U.S. lecturing Blacks on the importance of self-help programs. Like Booker T. Washington, Allensworth believed Blacks in America needed to become more self-sufficient.

But, if Blacks were going to stand on their own in America, they needed a safe place to do so–Allensworth wanted to provide that.

Following his own advice, he moved to Los Angeles with his family in search of California. Allensworth believed he could build a town dedicated to the prosperity of Black Americans. There weren’t many places Black people could live that allowed them to escape the clutches of Jim Crown, even in the north. But California was a new land, with hope and opportunity. All Allensworth needed now was a team.

Insert William Payne, a professor at West Virginia Colored Institute, Dr, William H. Peck, a Los Angeles minister, and J.W. Palmer, a Nevada miner.

Then men searched far and wide for the right plot of land until Allensworth decided on an area in southwest Tulare County. The land seemed to have an abundance of water and rich soil.

Source: Fresno Bee / Getty

On August 3, 1908, the all-Black town of Solito was born. Later that year the townspeople would change the name to Allensworth in honor of its most important founder. The town of Allensworth was a true gem and was far ahead of its time. It not only had a depot connection on the Santa Fe Railroad but also had an official town government called the Allensworth Progressive Association. The town held elections, as well as regularly scheduled town meetings. Allensworth was also a voting precinct and had its own school district, with a local school built with money raised by the community. The school included students from elementary to high school.

Since Allensworth prided itself on the importance of education, the town’s extracurricular activities were centered around the advancement of the Black mind. The town had a Women’s Improvement League and boasted a Debating Society, a Theatre Club, and a Glee Club.

The town thrived off of its agriculture. Allensworth’s economy was built around the farmers who lived in the surrounding areas. Allensworth had serval businesses including a bakery, a drug store, a barbershop, a machine shop, as well as a hotel.

Unfortunately, the rest of this story is more of a Greek tragedy than it is a fairytale.

In 1914, Allen Allensworth was killed after he was hit by a motorcycle during a trip to Los Angeles. The town was devastated but continued to prosper.

By the 1920s there were more than 300 residents that lived in Allensworth. It attracted Black soldiers, Black educators, and Black thinkers from all over the country.

But the town of Allensworth never made it.

Its biggest downfall, being a Black self-sufficient town in a white racist country.

For Allensworth to continue to blossom, it needed support from the surrounding white establishments, but that was far from the case.

The Pacific Farming Company controlled most of the land sales in the state. They frequently sold plots of land to Blacks at inflated prices and even refused land sales to Blacks after Allensworth began to boom.

The Pacific Water Company lied to Allensworth’s elected officials, promising the town the addition of water wells due to the lack of sustainable water sources. Instead of adding the water wells in Allensworth, they installed the wells in the neighboring white town, leaving Allensworth’s unusable.

Townspeople pleaded with the company to keep their promises and add the necessary wells, but the Pacific Water Company ignored their pleas. The long legal battle would end in a loss for the townspeople.

Since agriculture was so important to the way of life in Allensworth, once the water went, so did the residents.

The Santa Fe Railroad would also follow suit in helping to quickly destroy the popular Black town of Allensworth. They suspended the connecting rail line and diverted it to a neighboring all-white town.

With no water to farm and no transportation to grow, Allensworth ultimately became a ghost town, gone forever but most certainly not forgotten.

Today, in the place that once represented Black resilience, sits the Colonel Allensworth State Historic Park. The park works to continue the legacy of Allensworth and the ideals that Allen lived by. The organization Friends Of Allensworth also allows you to help promote the town’s legacy. It was created to raise awareness of the town of Allensworth, as well as to grow support for the park. If you would like to support the park click here.

How do you get a whole race of people to uplift themselves after years of persecution? You give them direction and show them anything can be achieved with determination and confidence in yourself. That was Colonel Allensworth’s true legacy

“Progress in human affairs is more often a pull than a push, surging forward of the exceptional man, and the lifting of his duller brethren slowly and painfully to his vantage-ground.” – W.E.B. Du Bois

SEE ALSO:

The Legend Of O.T. Jackson And The Black Ghost Town Of Dearfield, Colorado

There’s A Black Village Under Central Park That Was Founded By Alexander Hamilton’s Secret Black Son