Source: creative services / iOne Digital

There’s an ugliness in American history that few like to talk about. Stories from the past that resemble a horror movie more than they do the building of a nation. Sadly, many of the horrors in American history stink of racism.

MORE: The Haunting Of Lake Lanier And The Black City Buried Underneath

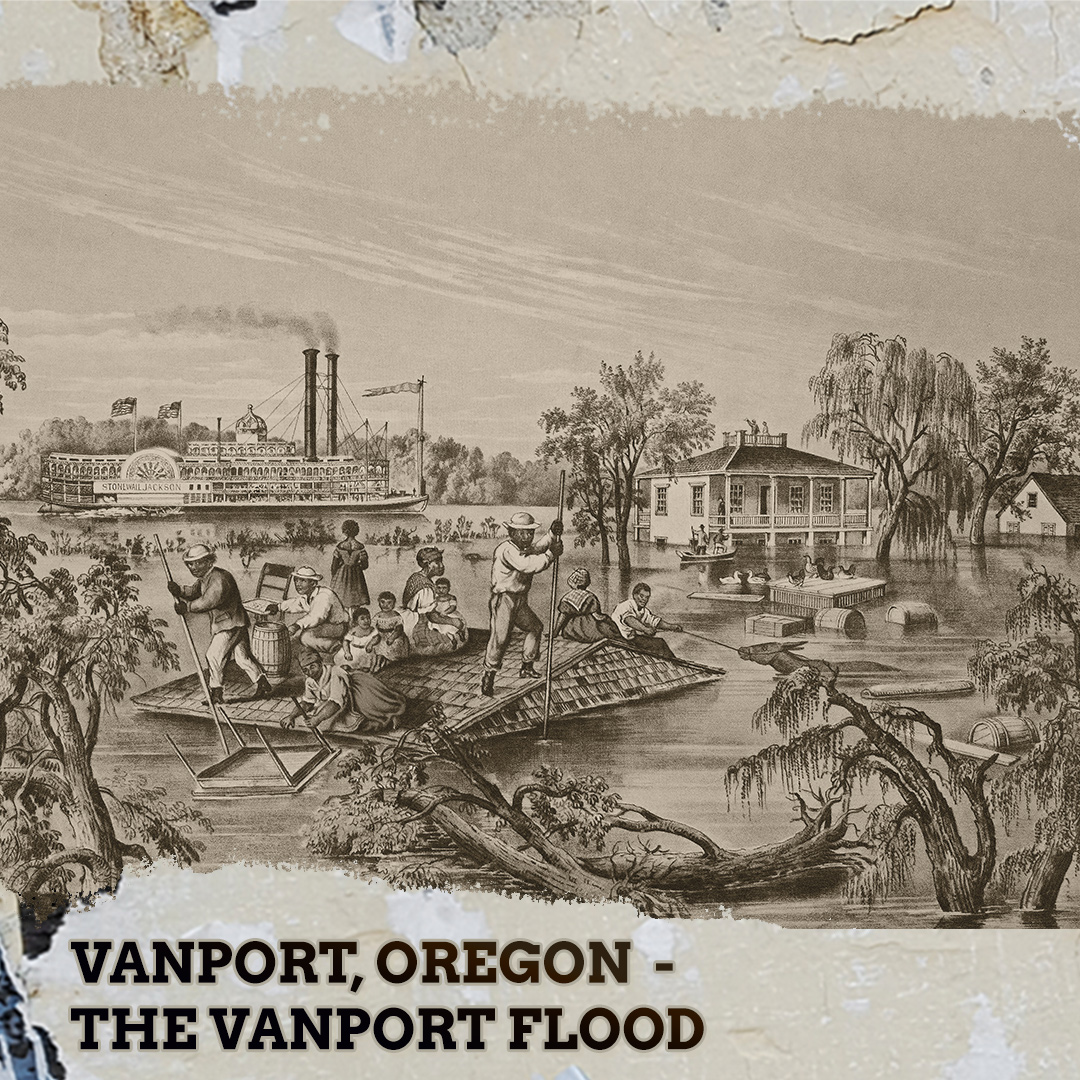

In the latest installment of Black Folklore, we dive into the story of the 1948 drowning of Vanport, Oregon.

Once the second largest city in the state, Vanport was founded because of racism, and then destroyed because of racism.

Oregon is one of the whitest states in America. Only 2% of the entire state is Black, well below the national average of around 13%. Portland, the biggest city in the state, is 6% Black. This is no coincidence.

On September 21, 1849, Oregon’s Territorial Legislature enacted a law that prohibited Blacks from entering the state.

The law specified that “it shall not be lawful for any negro or mulatto to enter into, or reside” in Oregon, with exceptions made for those who were already in the territory.

Although slavery was outlawed in Oregon on November 7, 1857, four years before the civil war would begin, racism still had its grip on white minds. In the same vote, voters disapproved of slavery by a wide margin but voted for an exclusion clause that once again banned Blacks from entering or living in the state, owning property in the state, and making contracts with businesses in Oregon. Whites feared that Blacks would “intermix with Indians, instilling into their minds feelings of hostility toward the white race.”

As a result, Oregon would become the only free state admitted to the Union that banned Blacks. It was not repealed by voters until 1926.

Oregon was successful in strategically creating a white utopian state, but that would all change once World War II rolled in. White men began getting drafted by the droves to fight overseas, which created a labor shortage in a country still developing its infrastructure.

During the Great Migration, Blacks saw this as an opportunity to create a better life for themselves and their families and many migrated to the northwest.

Portland became an ideal location for Blacks seeking employment during wartime America. Black men and women began arriving in Portland by the thousands. By the early 1940s, Portland’s Black population exploded and city officials suddenly had a housing crisis on their hands. Due to redlining, Blacks were only legally allowed to live in the Albina neighborhood of the city. But there just wasn’t enough space to fit Portland’s booming Black population.

City officials needed a way to fix the housing shortage, but also make sure to keep their discriminatory housing policies intact. One thing they didn’t want was to make Black families too comfortable, then they might not leave after the war was over. The established “white way of life” had to be protected and whites did not want Blacks staying in their neighborhood permanently. “Portland can absorb only a minimum number of Negros without upsetting the city’s regular life,” said the city Mayor.

The city eventually built 4,900 temporary housing units for some 120,000 new workers, but it wasn’t nearly enough.

Industrialist and owner of Oregon Shipbuilding Corporation Henry Kaiser needed the process to move faster. His shipyard needed workers immediately, so in 1943 he decided to build a temporary housing project on the Columbia River. The haphazard city of Vanport was completed in just 110 days, with a system of dikes as the only protection from the massive river.

The town, which was built on marshland, had 10,414 apartments and homes and was physically separated from Portland by the Columbia Slough.

The homes were cheaply made from wooden blocks and fiberboard walls and provided little comfort or privacy for anyone living in them. But this didn’t stop eager Blacks and whites from moving in. For many Americans, the opportunity meant consistent work and a means to a better way of life.

Vanport quickly grew into the second largest city in Oregon, rivaling its neighboring Portland. It was also the largest housing project in the country. At its peak, it was home to 40,000 workers, more than 6,000 of whom were Black. But everything would change for Vanport in 1948.

A snowy winter, mixed with a warm and rainy spring caused the Columbia River to reach dangerous heights. On May 25 of 1948, the river had reached 23 feet, eight feet above flood stage level. City officials began monitoring the dikes but didn’t issue a single warning to residents. Instead, the Housing Authority of Portland and the United States Army Corps of Engineers told residents the city need not worry about flooding because the dikes were not in jeopardy of collapsing, but that was a lie. While reassuring Vanport residents that the city was safe, the Housing Authority of Portland secretly removed files and equipment from their offices in the city. They also relocated 600 horses from a nearby racetrack.

On the morning of May 30, 1948, the Housing Authority sent flyers to the residents of Vanport once again affirming the dikes were safe. By 4:17 p.m the dikes began to give way. At first, it was just a crack about six feet wide. But that crack rapidly expanded and before residents even knew what was happening, that little crack had grown into a 500-foot gap in the dikes. Thousands of homes were washed away in the blink of an eye. Within ten minutes the entire city was gone, destruction and devastation the only thing left. There was no warning from law enforcement or city officials and residents lost everything. Hundreds of innocent people lost their lives. If it wasn’t for students and faculty from Vanport College alerting residents that flood waters were on their way, many more would have died.

18,500 residents were displaced, and roughly 6,300 were Black.

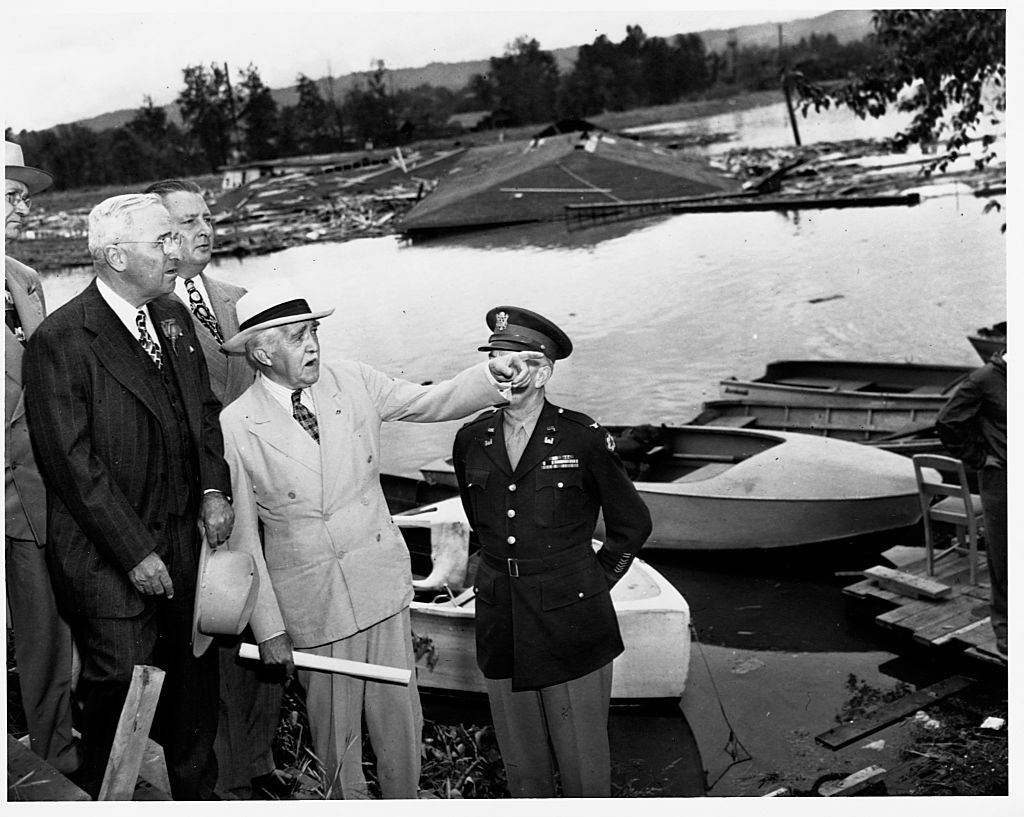

Source: President Harry Truman, left, listens as Gen. Philip Fleming, Federal Works Administrator, explains the damage caused by the sudden flood on May 30 at Vanport, Oregon. The president visited the area during his inspection of the Columbia River flood damage. Source: CORBIS/Getty

Vanport could have been saved if white people wanted it to be. It’s hard not to believe that this was the plan for Vanport all along. Temporary housing built atop marshland, building materials that weren’t worth a damn–Vanport was never intended to succeed, it was just a schemey way to use Blacks for their labor and then let nature dispose of them so the whites didn’t have to do it.

Today, like so many other drowned Black towns, Vanport has been replaced with beauty so that white people in Portland do not have to be reminded of their racist ancestors. What was once a booming city with so much promise for Black residents is now a sprawling park with golf courses, baseball fields, and lush greenery. The only thing there to remind you of the horrors from the past is a plaque barely visible to the naked eye.

I mean who wants to be reminded of their ancestors’ racism and bigotry while they’re taking a morning jog in Delta Park?

SEE ALSO:

Brooklyn’s Lost Black City Of Weeksville: A Hidden Gem Of Pre-Civil War Black Excellence

The Legend Of O.T. Jackson And The Black Ghost Town Of Dearfield, Colorado