Like journalists everywhere, the staff of the San Quentin News cover news, sports and the local arts scene. But these reporters are pen men with a difference.

They work for a paper written by and for inmates of San Quentin State Prison.

“When we first started, a lot of people were real dismissive of the paper,” said Michael R. Harris, editor-in-chief of the San Quentin News.

“Once we started printing the paper … you see this prison come to life in terms of cooperation, in terms of, hey, this is an opportunity to be able to tell the stories from your perspective and also allow the rest of the world to see what’s happening here,'” said Harris, 47, serving 25-to-life for attempted murder.

The revival of the News last year, after a hiatus of nearly two decades, goes against a national trend of shrinking prison journalism, said James McGrath Morris, who wrote about the penal press in his book “Jailhouse Journalism.”

“San Quentin is sort of like a flower coming up in a barren garden,” he said.

Lt. Rudy Luna, the program sponsor, said it is not clear why the San Quentin News quit publishing, but the impetus to restart it last year came from then-Warden Robert Ayers. The plan was to teach inmates skills and keep the community informed.

“A lot of the issues with inmates are just lack of information and by putting that information out and telling them we have programs available, maybe we can bring them on board,” said Luna.

Being an inmate reporter means unique challenges — no direct access to the Internet, no ability to make a quick phone call or send an e-mail. It also means having thousands of potential critics living right next to you.

Some of the strongest criticism comes from correctional officers, who may be skeptical of the inmate reporters’ objectivity or just do not support providing this kind of outlet to convicted criminals, Luna said.

At the Sacramento-based California Correctional Supervisors Organization in Sacramento, Pat LeSage, chief operations officer, said officials have not reviewed the San Quentin paper and cannot comment in depth on its merits.

In general, “our concern would be that a publication going out to the public written by inmates needs to be closely monitored to ensure the safety of the staff, to ensure that a one-sided view is not moved forward to the public,” she said.

Morris is a supporter of prison newspapers.

“Unless we’re planning on keeping these criminals locked up forever, some effort must be made to assist them in re-entering the public world where there’s freedom of the press and freedom of speech,” he said.

The tradition of prison journalism was established in 1800 in a debtor’s prison in New York, and eventually grew to hundreds of papers across the country, says Morris.

Some papers were independent, others sanctioned by administrators who believed a paper could serve as a rehabilitation as well as communication tool.

But in the 1960s and 1970s, the prison press became more confrontational, matching the times, and papers became a problem rather than an asset at a time when prison authorities were pressed by growing overcrowding problems, Morris said. Papers also began running into obstacles such as a lack of paper for the press run or a lack of ink.

About 50 or 60 papers are left compared to 30 years ago when “pretty much every prison had one,” said Paul Wright, a former Washington State prisoner who started the independent Prison Legal News in 1990.

“It’s a pretty sad state of affairs,” said Wright. “It’s something that I don’t think has been very good for anyone.”

The San Quentin newspaper has a staff of four, although all inmates are invited to contribute. It is printed by inmate employees of the prison print shop and is hand-folded, a formidable job considering enough are printed for the prison population of more than 5,000.

Steve McNamara, retired publisher and editor of the Pacific Sun news weekly in Marin County, is one of several volunteer journalists who serve as mentors to the staff. He thinks the inmate journalists have been “astonishingly adept,” at learning how to report, write and lay out a newspaper.

Each edition contains straight news, such as an analysis of recent ballot initiatives, plus puzzles, poetry and sometimes helpful tips, such as how to cool a soda using a wet sock. Stories in recent issues have ranged from an interview with a former prisoner turned social activist to an account of computer classes at the prison.

So far, there have been no big censorship battles, although Luna recently vetoed a drawing as vulgar.

A watershed event for the San Quentin paper came when an inmate wrote in the January issue about conditions in “the hole,” the one-man cells reserved for inmates under discipline. Their newspaper adviser recommended holding the story until a prison official was interviewed to balance the story.

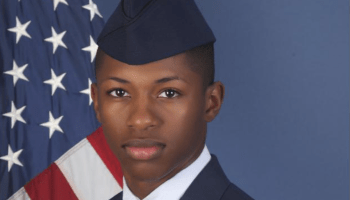

The final product still drew plenty of criticism from correctional officers who did not think balance was achieved but, “to me it was great because actually that story legitimized us,” said Aly Tamboura, who is serving a 14-year sentence for assault and is the paper’s design editor. “The bottom line is it did what the news is supposed to do.”

Luna does not have a figure for exactly how much it costs to run the paper, which falls under the prison’s general education budget. With the state facing a $24 billion deficit, Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger has proposed laying off 5,000 state employees, the majority in the corrections department. Luna is not sure if state cuts spell trouble for the paper.

Other papers may be struggling for circulation. But not this one, says Tamboura, 42.

When the paper’s handed out, “guys just run,” he says. “They want the paper.”