Why Black History Month Matters At 100 More Than Ever

- Black History Month started in 1926 as a way to challenge the erasure of Black history in education.

This year marks the 100th anniversary of Black History Month. As we reflect on our stories, this centennial is not only a moment of celebration but a call to urgency, a reminder that protecting, preserving, and uplifting Black history matters now more than ever.

Let’s take a look back at how we got here and why this year carries such deep significance.

How did Black History Month start?

Black History Month traces its roots back to 1926, when historian Carter G. Woodson and his Association for the Study of Negro Life and History launched Negro History Week. Woodson, the son of formerly enslaved parents, understood something radical for his time: that the absence of Black history in American education wasn’t accidental; it was structural.

Woodson witnessed firsthand that racial discrimination was not simply a social reality; it was enforced by law. Segregation was codified across nearly every aspect of public life, with states mandating separate transportation, schools, and public spaces for Black and white Americans. From buses and trains to classrooms, water fountains, hospitals, and even courtrooms, these laws institutionalized inequality and shaped daily life, reinforcing a system designed to exclude and marginalize Black communities.

In response to this reality, Woodson created Negro History Week, driven by a sense of urgency and the belief that change had to begin with education. He was determined to ensure that Black children, and the nation as a whole, were exposed to Black history. Woodson chose the second week of February to coincide with the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass, figures long honored within Black communities.

Negro History Week was not born in a vacuum. The 1920s marked a flourishing of African American cultural expression through the Harlem Renaissance, as noted by the National Museum of African American History & Culture. Writers such as Langston Hughes, Georgia Douglas Johnson, and Claude McKay explored the joys and struggles of Black life, while musicians like Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, and Jimmy Lunceford captured the rhythms of a changing urban America shaped by the Great Migration. Visual artists, including Aaron Douglas, Richmond Barthé, and Lois Mailou Jones, created powerful images that celebrated Black identity and offered affirming representations of the African American experience.

Woodson hoped to build on this momentum, using Negro History Week to further spark curiosity, pride, and sustained engagement with Black history and to challenge a national narrative that erased Black contributions, giving Black communities a way to tell our own stories in classrooms, churches, and civic spaces.

Teaching Black history was an act of resistance against a society invested in forgetting.

From A Week To A Month: How Black History Month Expanded

What began as a week quickly grew beyond Woodson’s original vision, not because the work was finished, but because it became clear that a week was never enough. By the 1960s and ’70s, amid the Civil Rights and Black Power movements, educators and students pushed for broader recognition. In 1976, the U.S. officially designated February as Black History Month, with President Gerald Ford recognizing the month, according to AP News.

The expansion reflected both progress and tension. On one hand, Black history gained national visibility. On the other hand, it risked being contained, treated as an add-on rather than as foundational to American history. The month became a compromise: acknowledgment without full integration.

Still, communities used the space creatively, building archives, hosting lectures, preserving oral histories, and insisting that Black history was not a niche subject, but central to understanding the nation itself.

What The 100-Year Milestone Matters Right Now

This February, we mark the 100-year anniversary of this incredible commemoration, and the work of preserving, protecting, and honoring Black leaders and communities is far from finished. Reaching this milestone is not just symbolic; it’s urgent. We are living in a moment where Black history is actively being censored in schools and other educational institutions, where DEI initiatives are under attack, and where deliberate historical erasure is becoming policy, not coincidence.

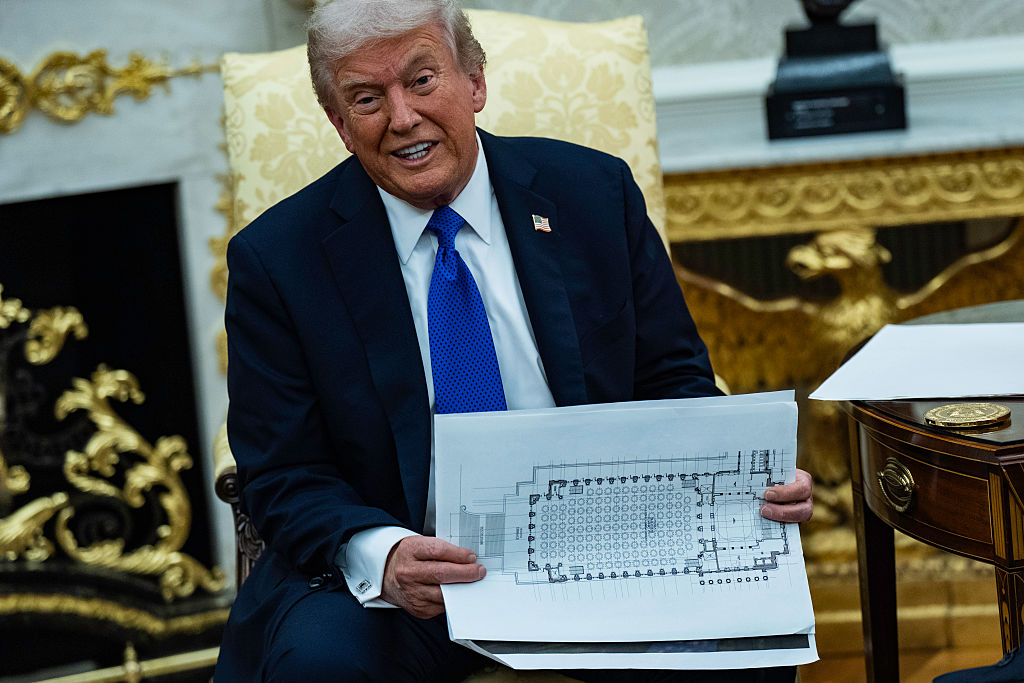

In 2025, President Donald Trump signed “Ending Radical Indoctrination in K–12 Schooling” (Executive Order 14190), an executive order aimed at removing what it labels “specific ideologies” from public education and reorienting schools toward so-called “patriotic education.” In practice, the order significantly restricts how Black history, and particularly the history of slavery and systemic racism, can be discussed in classrooms. By redefining discussions of equity and racism as “discriminatory,” it creates a chilling effect on honest teaching. That we are living in a time when truth itself is treated as a threat should alarm us all.

Across the country, school districts are banning books, limiting how race can be discussed, and reframing accurate history as “divisive.” The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison and All Boys Aren’t Blue by George M. Johnson are just a few of the many works that have been targeted. These aren’t isolated decisions; they are part of a broader effort to control the narrative of America’s past, and we can’t let it happen.

While Black history should be taught and celebrated year-round, Black History Month remains a powerful and necessary space to ensure our stories are told truthfully and to push back against policies designed to erase the contributions and sacrifices Black Americans have made.

The centennial forces an essential question: What happens if we stop telling these stories? The answer is already visible. When Black history is minimized, inequality becomes easier to justify. When contributions are erased, power appears natural rather than constructed.

Remembering Black history, publicly, loudly, and accurately, is not nostalgia. It is a defense against revisionism. It is a refusal to allow the past to be rewritten to serve the present.

What Black History Needs To Be In Its Next 100 Years

If we want to protect Black history, the next century of work can’t look like the last. It must be broader and deeper. That means embracing digital history, online archives, podcasts, social media storytelling, and interactive maps that make history accessible beyond academic gates. It means prioritizing community-led storytelling, where everyday people document their own neighborhoods, families, and movements instead of waiting for institutional validation.

It also means centering local histories. Black history doesn’t live only in national heroes; it lives in barber shops, churches, kitchens, protests, classrooms, and small towns that never make it into textbooks. NewsOne prides itself on leading the charge to document and uplift our stores.

And finally, Black history must move beyond February. The goal has always been year-round integration, where Black experiences are woven into how we teach literature, science, politics, labor, and culture, rather than reduced to a single month.

If the first 100 years were about fighting to be seen, the next 100 must be about refusing to be confined. Black history isn’t a supplement. It’s a foundation, and the future depends on how well we protect it.

SEE MORE:

Urban One Presents ‘REPRESENT: The Next 100 Years Of Black History Month’

Death Of Deep Ellum: How Racist Urban Planning Erased Dallas’ Black Cultural Hub