Black Granny Kissing Trump At BHM Event Was A Mammy Moment

The Black Granny Kissing Trump During A Black History Month Celebration Was a Mammy Moment

Have y’all ever heard of Al Jolson?

He was that early-20th-century Broadway star and Hollywood entertainer who built an empire smearing burnt cork on his face and singing in blackface about “Mammy.” He was the voice behind The Jazz Singer, the first major talking picture.

Under hot stage lights, he stretched his arms and mouth wide and famously belted out: “Mammy… My little Mammy… I’d walk a million miles for one of your smiles…”

In other versions, he crooned lines like, “I’m comin’ home, Mammy… to you.”

The lyrics were simple, almost childlike, but emotionally loaded. Here was a grown white man performing longing for an enslaved Black woman cast as comfort, refuge, and unconditional love for white folks. He wasn’t longing for justice or equality. He was longing to be soothed, reassured, and to land somewhere soft when the world felt hard.

That’s what made the song powerful and insidious as hell. It reduced the Black woman to emotional utility and as a permanent sanctuary whose purpose was to absorb white distress and return warmth. The repeated “Mammy” line wasn’t just melody; it was instruction. She is to be the anchor and the comfort, and Mammy will always take you back, no matter the scale of harm done to her or her people.

White audiences didn’t just weep and applaud; they surrendered to it and let it baptize them. Because “Mammy” wasn’t a mother. She was a psychological sedative. A racial hallucination dressed up as love. Loving without limits, loyal without conditions, forgiving without memory, and politically lobotomized. Mammy exists solely to cleanse white guilt and re-center white innocence.

And white racists needed that fantasy. They needed and still need Black love to survive their own brutality. Because domination without affection is too naked and violence without validation is too honest. If the people you exploit do not love you, then you have to confront what you really are. So the myths, tropes, and songs step in. And the Mammy steps in with her arms wide, eyes soft, absorbing the harm and returning comfort.

Awww, there, there now

Let me hold the lie for you.

Let me carry the guilt so you ain’t got to.

Let me make you human again.

That was the magic of the intoxicating Mammy myth. Mammy was the delusion that no matter what was stolen, whipped, lynched, bombed, segregated, or burned, there would always be a Black woman waiting with open arms and zero reckoning. Always ready to murmur, “You’re still good. You didn’t mean it. Come home. I still love you.”

Y’all see the pathology?

Now, fast-forward from burnt cork and vaudeville stages to chandeliers and cable news inside the White House during Black History Month. A month carved out of blood and boycott. A month built on rebellion, resistance, and refusal. A month about the enslaved who ran. The students who sat in. The women who organized. The elders who marched and shot back. A month meant to remember refusal, not compliance. Struggle, not flattery. Collective courage, not personal proximity to power.

And there, in the East Room, under gold drapes, flags, and presidential seal backdrops, stood Forlesia Cook, a Black grandmother from Washington, D.C. She stepped up to the mic with her church-lady cadence and Sunday hat energy without the hat. She had the kind of voice that usually introduces the choir, calls for offering, or shares a fiery testimony about the goodness of the Lord.

And what does she say?

First, she asked to hug the president. “Yes, you can,” he said. She leaned into the hug and kissed him on the cheek.

Ughhh.

She kissed and hugged a man who once took out full-page ads calling for the execution of the Exonerated Five (then the Central Park Five), who were falsely accused of rape. A man who led the birther conspiracy against the first Black president. A man who referred to majority-Black nations as “shithole countries.” A man who told four congresswomen of color to “go back” to where they came from. A man whose Justice Department fought against fair housing claims involving Black renters. A man who called white supremacists in Charlottesville “very fine people.” A man accused by multiple women of sexual assault. A man who built a political brand on racial resentment.

“I like her,” he said.

“I like him too,” she replied.

Do y’all hear the call-and-response of delusion?

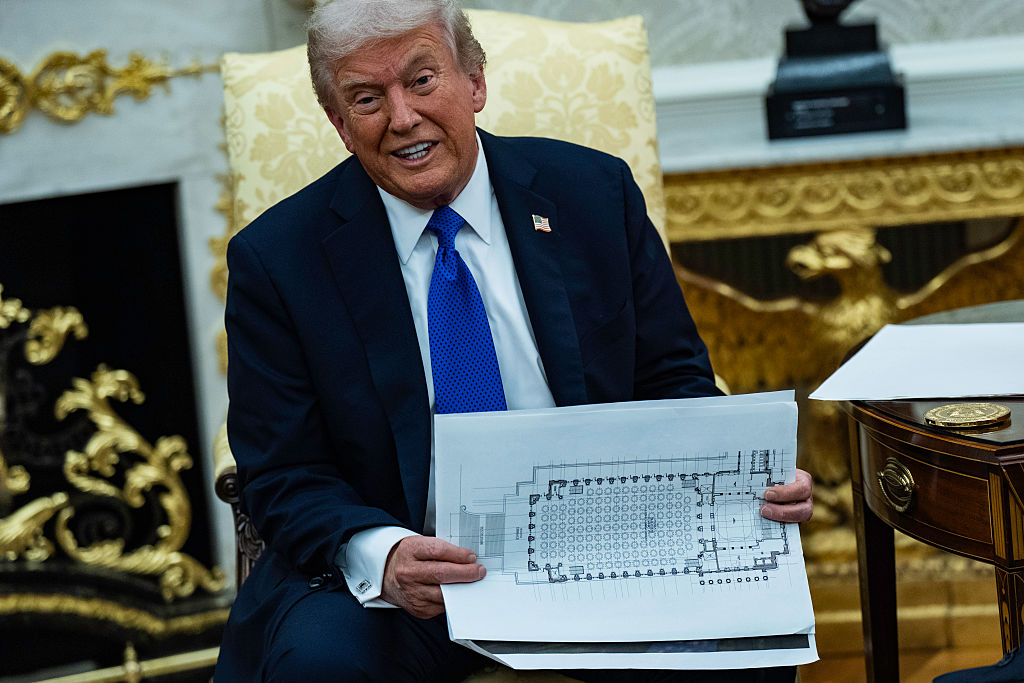

And notice how Trump acted in that moment. Did you see the grin stretched wide and satisfied? Shoulders slightly back. Chin lifted. That slow, pleased nod of a man being publicly affirmed in a way he knows carries cultural weight. He didn’t look awkward or recoil. He basked.

He let the hug linger just long enough for the cameras. He let the kiss land and the symbolism marinate. There was a blush of triumph in it. He had the smirk of a man who understands spectacle and what it means, politically and psychologically, to be embraced by a Black grandmother during Black History Month.

It was a modern minstrel reversal. Not with burnt cork or a stage song this time. But with the same energy that animated Al Jolson under hot lights. Jolson performed longing for Mammy. Here, Trump didn’t have to perform because the affirmation came to him.

Jolson sang, “I’m comin’ home, Mammy.” This time, the Mammy moment came to him. And we got a visual absolution delivered in front of the nation.

Then Forlesia Cook leaned fully into the script:

“One thing I like about him, he keeps it real, just like Grandma. I appreciate that because I can trust him, because he tells exactly how he feels and what he thinks. Thank God for this president. I love him.”

I love him, she said. During Black History Month. Standing in a building constructed by enslaved Black labor. She offered emotional cover, wrapped him in grandmotherly validation, and told America that she trusts him. That she loves him. That she doesn’t want to hear “nothing you got to say about that racist stuff.”

That’s the part that turns the stomach. Because the kiss wasn’t private. It was symbolic and theatrical. In a month meant to honor resistance to white supremacy, a Black elder publicly cradled one of its most visible modern avatars of racism, and the room smiled. Because nothing soothes like Black approval. Nothing disinfects accusation like a Black grandmother’s embrace.

Awww, there, there now.

He’s still good.

He keeps it real.

You can trust him.

Then she put the seal on it: “And don’t be looking at me on the news hating on me because I’m standing up for somebody that deserves to be stood up for. Get off the man’s back. Let him do his job. He’s doing the right thing. Back up off of him.”

Why did she feel the need to say that?

Because she knew.

She knew it would land sideways. She knew that publicly hugging and kissing this racist president during Black History Month would not read as harmless grandmotherly affection. It would read as betrayal to some, theater to others, and ammunition to many. And so that defensive preamble was a preemptive measure of insulation.

You don’t tell people not to “hate” on you unless you already anticipate the heat. You don’t wave off “that racist stuff” unless you know the receipts exist. You don’t shout “back up off of him” unless you understand you’ve stepped into a storm. She anticipated critique and tried to smother it before it formed. Which means, on some level, she understood the symbolism. And did it anyway.

And let’s be honest about something else: this all felt staged. You know it, and I know it. It wasn’t necessarily scripted word-for-word, but engineered for impact. A Black grandmother. Black History Month. Cameras rolling. A hug. A kiss. A testimonial about trust and none of that racist stuff was all about optics.

Because while this administration wages war on how Black history is taught and preserved, attacks DEI initiatives, hollows out civil rights enforcement, and frames conversations about systemic racism as “divisive,” what better counter-image than a smiling Black elder saying, “I love him?”

For the MAGA base, her defense functions as validation. It says: See? The racism accusations are exaggerated. See? We’re embraced. See? Even Black grandmothers trust him.

Her body became a prop in a larger narrative designed to soothe a base that bristles at being called racist while supporting policies that disproportionately harm Black communities. The embrace becomes evidence, the kiss becomes cover, and the testimonial becomes a shield. It’s political laundering wrapped in church-lady cadence.

And that’s why it felt less like a spontaneous moment and more like a perfectly timed cultural sedative.

What we witnessed during that celebration was maternal sanction. That was a Black elder stepping into the cultural role American mythology carved out generations ago. She was the soft-voiced validator of white power. In a room draped in symbolism, during a month meant to commemorate rebellion against white supremacy, a Black grandmother offered comfort to the presidency most associated with racially polarizing rhetoric in modern politics.

Awww, there, there now.

He keeps it real.

You can trust him.

Back up off of him.

And that’s the part we cannot afford to romanticize. Because what we witnessed was not just affection. It was absolution.

It was the recycling of a script older than Reconstruction. The same emotional choreography that made Al Jolson a star. The same fantasy that powered The Jazz Singer. The same mythology that taught America that no matter the brutality, no matter the policy, no matter the harm, there would always be a Black woman ready to soothe white anxiety and restore white innocence.

Black History Month is supposed to honor Harriet’s revolver. Ida’s pen. Fannie Lou’s unbreakable voice. It is supposed to honor resistance that made white power uncomfortable. Instead, in that East Room, we saw comfort offered to power. That is how the Mammy myth survives. Not in burnt cork. Not in minstrel songs. But in spectacle. In podium moments. In carefully televised affection.

But here’s the truth that refuses sedation: Black love is not a laundering service for white supremacy. Black elders do not get to sanctify harm simply because their voice trembles with church cadence.

And Black History Month is not a stage for reenacting America’s favorite racial delusion that proximity equals progress, that affection equals absolution, that a kiss can erase a record.

If Harriet Tubman carried a revolver to protect collective freedom, then we need moral clarity for those who endanger collective memory. Because some of us are done whispering “there, there.” Some of us are done holding the lie because Black history is not comfort, it is confrontation.

Dr. Stacey Patton is an award-winning journalist and author of “Spare The Kids: Why Whupping Children Won’t Save Black America” and the forthcoming “Strung Up: The Lynching of Black Children In Jim Crow America.” Read her Substack here.

SEE ALSO:

Why What’s Happening At Texas Colleges Matters For HBCUs

Perspective: Without Jesse Jackson, There Is No Barack Obama