Harry Belafonte: Jamaica, Farewell

Jamaica, Farewell

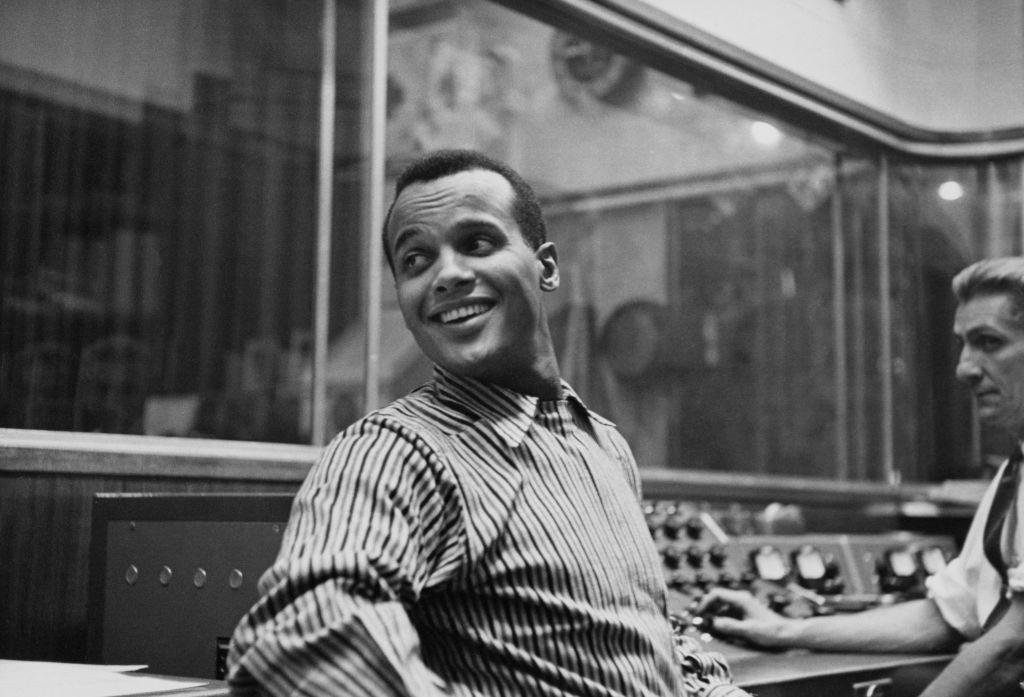

Source: Archive Photos / Getty

It really doesn’t matter that we knew for some time that his death was imminent. He’d been frail for years, and for years, each time I asked Susan Taylor, who’d formally introduced us more than two decades ago, if perhaps there was an event Mr. B. could attend with us, she’d tell me he wasn’t well enough. But in the way I could never see my own father’s strength leaving him, not even when he was in hospice, neither could I prepare myself to hear that Harry Belafonte—artist and organizer, father, husband, son and friend—had drawn his final breath. In many ways, and despite all the times we’d spoken, I really only knew him a little bit, but it was for a very long time and I loved him from the moment we first sat down together in 2002. It’s been a week now since he died peacefully, surrounded by his loved ones on April 25, and the charge of gathering together all the words, all the feelings in a single neat tributary still seems nearly impossible. But Mr. B pushed himself and those he engaged, to alchemist-like, transform the elements, which is why my story of him begins with the very first encounter I ever had with the man we all saw turn the lead into gold.

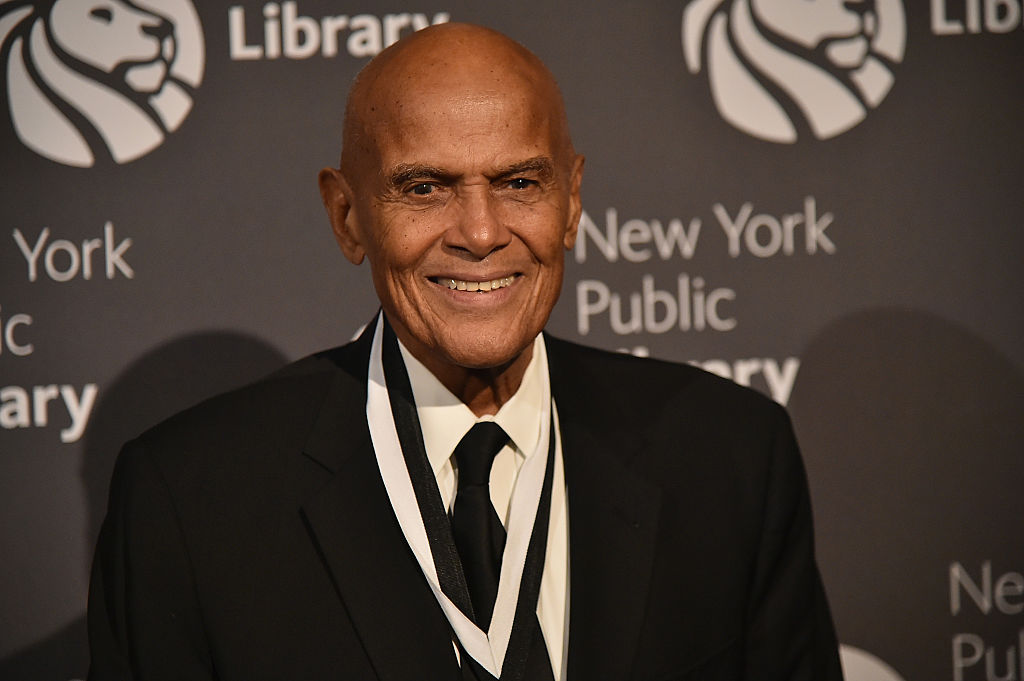

Source: Theo Wargo / Getty

West Side Story

I was 12 and although I didn’t realize it then, Mr. B. and I lived about eight blocks from each other on West End Avenue in the New York City of my childhood. Our encounter was purely accidental. I’d gone over to 300 West End Avenue, the building where the Belafonte’s lived at the time, because my boyfriend, Miles, also lived there with his family—which included his father, the legendary double-bassist, Ron Carter.

Three hundred was the kind of elegant and exclusive building where the doorman had to turn a special key in the elevator for you to get to the apartment you’d been invited to. But instead of sending me to the Carter home, he mistakenly sent me to the Belafonte home and suddenly there he stood, Mr. B.! We were both confused, but he was composed. Me, less so. He didn’t know who this girl standing before him was, but I certainly knew who he was: the man whose music played in our house—and the only man, besides my father, who ever made my mother get that sort of glint in her eye. I stammered, explained who I was and who I was there to see, and moments later I was whisked down to Miles’s apartment where we played pool that afternoon and maybe even kissed.

Harry Belafonte pushed himself and those he engaged to, alchemist-like, transform the elements.

But the real story isn’t about Miles or the accidental encounter with Mr. B. It’s about the strategic thinking and brilliance of Harry Belafonte, a man who was born into New York’s specific sort of poverty. As a child, he lived between New York City and Kingston, Jamaica, and although likely being the most erudite, eloquent man with whom I’d ever spoken, he never graduated from high school. And despite him being a person who had known and worked with the giants of the 20th—and 21st—century Black and other movements for freedom—not to mention the most renowned artists across three generations—when I asked him if there was one person whom he most admired, he took a long pause, inhaled, closed his eyes and then opened them and said, “My mother was a washer woman who wept from the inability to give her children more…My mother…”

Source: Pictorial Parade / Getty

But for all that he may have lacked in childhood, somewhere the ability to develop exceptional critical thinking skills was poured into him. And that’s why 300 West End Avenue is important to know about.

In the late 1950s when it was almost impossible for Black people to rent an apartment in many parts of New York City, particularly middle and upper-middle class neighborhoods, Mr. B., aware of the racism, rented the penthouse at 300 West End through a friend who I suppose was white. He was probably the most famous Black male artist in the world at the time–and the first single artist to sell 1 million records. But Up South is Up South. When the building’s landlord—who was the son of the racist murderer and decades-long dictator of the Dominican Republic, Rafael Trujillo—found out, he told Mr. B. he had to leave.

Mr. B.’s response was to get together some partners, form a corporate entity, and buy the building out from under Trujillo. They took the property co-op and got others—including other Black artists—to move in. The Carters weren’t the only Black artist family who lived there. Lena Horne did for a time, too. But more, that act of taking American capitalism and making it an act of justice, changed the face of Manhattan’s West End Avenue community. My family would move to the neighborhood a little over a decade later, and by the time I was growing up there at 140 West End Avenue, it was a fairly integrated and solidly middle-class area. Our downstairs neighbor was Duke Ellington, who, weirdly enough, had also been my parents’ neighbor in their previous apartment near Harlem, in the years before Black folks made it downtown, to the place Mr. B helped open up for us.

Source: Johnny Nunez / Getty

A Tale of Two Jamaicans

But I won’t learn that story about him—or see him again in person–until I am an adult, a journalist working at Essence, assigned to interview him roughly a year after the September 11 attacks in New York, D.C. and Pennsylvania. The United States was poised to go headlong into a war with Iraq, a country that had nothing to do with the horror that occurred on that clear, bright Tuesday morning.

Harry Belafonte, despite harsh criticism for his positions, never shrunk, never smalled himself up. And no one silenced him.

But in the wake of the 2001 attacks, America was teetering between understandable shock and grief but also a vulgar expression of vengeance rooted in an even uglier expression of white nationalism. People in big cities and small towns doubled down on their existing anti-Arab, anti-Muslim hatred. There was little room for rational thinking or facts in a society that is arguably the most undereducated and politically unsophisticated of any in the West.

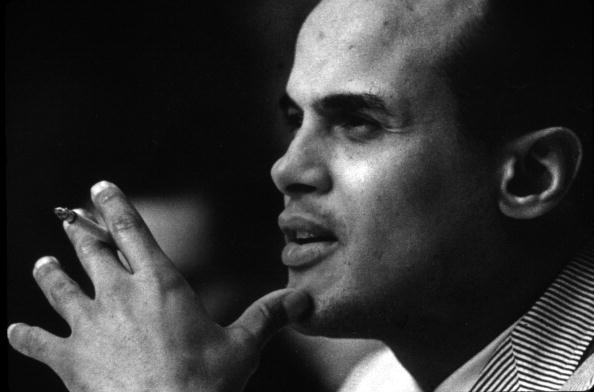

Source: Bettmann / Getty

Which is to say that it wasn’t difficult to get support for the war despite it being based on clearly questionable—later famously disproven—claims by the Bush Administration about Iraq having weapons of mass destruction. Colin Powell, who was the Secretary of State at the time, helped smooth the rough edges when he, a four-star general who like Belafonte, was a handsome, Black man whose family hailed from Jamaica–but who unlike Belafonte, was loved across color and party lines–said it was true. Iraq had the weapons, he said, and war against the nation was justified. People believed Powell to be a man of good character. His words—his lies—carried weight. I didn’t know him. Can’t speak to his character. But I do know that he sat before the United Nations and on behalf of two white men—George Bush and Dick Cheney—propagated their false assertions–lies–something to which he would later admit. No matter. America went to war and stayed at war for the next 20 years. Estimates put Iraqi deaths at over 1 million people, most of whom were civilians.

From the beginning, though, Mr. B, not only opposed the war, but called Powell a house slave. And he refused to back down from the statement despite wide criticism. Most often critics dismissed Mr. B. as an anachronism. But he wasn’t worried about anyone’s approval. He’d long ago diversified his income with real estate and other investments, making his dependence on white approval a matter of little importance. And his critics would learn that far from being an anachronism, Belafonte was, as the dictator’s son learned, a master strategist. He played chess when everyone else was playing checkers, and he operated from a blueprint that was a Venn diagram where justice, love and perhaps above all, truth, met.

Source: MediaNews Group/Boston Herald via Getty Images / Getty

The Belafonte Blueprint

But more than the war or Secretary Powell, what I remember most from that first interview, was Mr. B. talking about the late actor, scholar, athlete, attorney and humanitarian, Paul Robeson. He and Mr. B. were friends, close ones, and even as I write these words now, decades later, I can still hear the anguish in Mr. B.’s voice as he talked about Robseon’s final years, the isolation he was in, the pain.

Artists, he said, are the gatekeepers of truth.

The sadness Mr. B.’s felt for his friend was so present, so palpable that day, that it brought tears to my eyes. He talked about how viciously the U.S. had gone after Robeson who’d been called before McCarthy’s House on Un-American Activities in 1956 and refused to sign an affidavit affirming that he was not a Communist. But more powerfully, more painfully, Mr. B. talked about all the ways Robeson had been abandoned by the very people whose rights he’d fought for. Even still, Robeson held forth his truth and for that, America took his career, his social standing, his wealth and—at one point—almost his life. During the 1960s, post-McCarthyism but still during the height of America’s cold war with the then Soviet Union, Mr. Robeson slit his wrists one night, in an attempt to end his suffering.

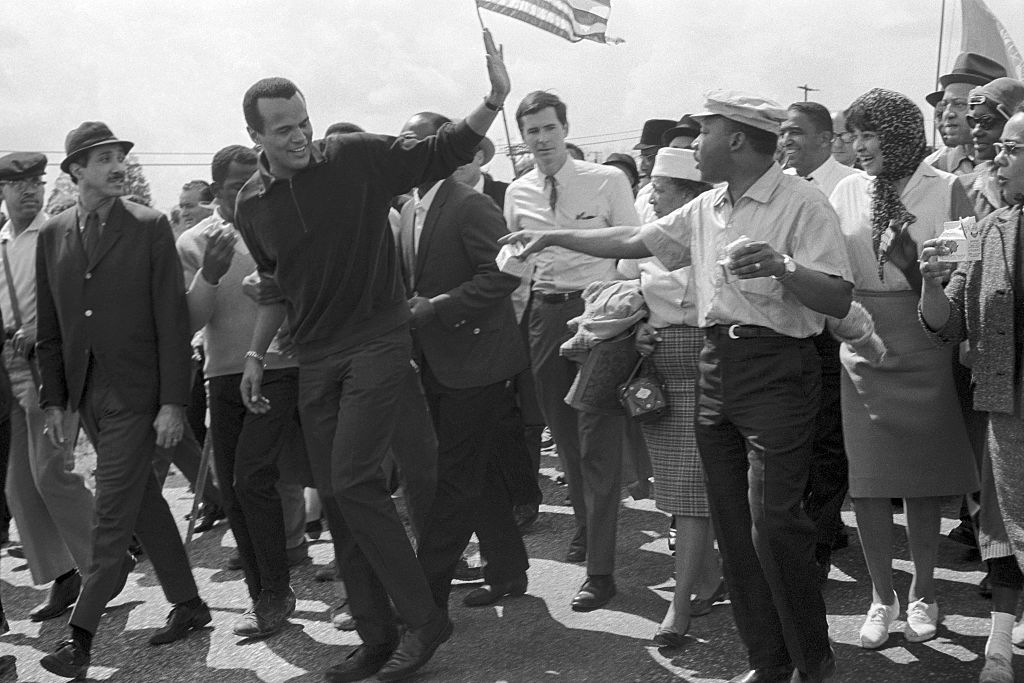

Harry Belafonte waves to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. as he leaves a column of civil rights Selma-to-Montgomery marchers on March 24, 1965. | Source: Bettmann / Getty

He survived, though and lived another decade or so. But it was a half-life, a lonely life, a life not befitting one of the greatest minds and spirits to ever grace this planet. And no, I don’t know why Mr. B brought up Robeson that day. Perhaps he could hear the drums of American white supremacy banging just outside his own door. Or perhaps he was unintentionally processing out loud what he would do as they were coming for him so that he didn’t live out his final years in the way Paul Robeson had been forced to live out his.

Or, perhaps he told me about Robeson as a way of sharing that strategy of his, that Belafonte Blueprint for Victory. Because despite the harsh criticism that Mr. B. faced following his remarks about the war and Powell, he never shrunk, never smalled himself up, never silenced himself. And no one silenced him. He continued to call it as he saw it with integrity and class—in print, in broadcast interviews and even in town halls with Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama, where he said that despite being a lifelong Democrat, the Party was in moral decay and he only agreed to sit with them in the hope that it could be salvaged. Later, after Obama’s election, Mr. B.’s initial support of the history-making president waned—and he said so. And at a White House event when Obama reportedly implored his elder to “C’mon man, can’t you give me some slack?” Mr. B. responded, “What makes you think I haven’t?”

That was the truth teller in him. The justice seeker.

Source: Patrick McMullan / Getty

Gatekeepers

But there was this other part of the strategy, this other thing he did. And that was the love part.

He chose us.

Us being the generations behind him.

Us being people from all stations in life.

Which is to say that I didn’t only speak with Mr. B as a journalist. I met with him in rooms as an organizer, an advocate, where other young organizers and advocates were, where other young artists and writers were. Some of us were just out of prison. Some had spent entire childhoods in gangs. Some of us never knew what love felt like until they felt it there in those rooms where Mr. B. sat and talked with us. They said so, even as we discussed hard topics—mass incarceration and poverty and racism. And every time I was in a room with him, no matter what the conversation, Mr. B. spoke as a true artist would—in a way that gives new meaning to old ideas. His words and ideas were alive and bold and fearless, completely unafraid of imagining another world into being.

Artists, he said, were the gatekeepers of truth.

Source: Ray Fisher / Getty

And we, the young people before him, were issued at every turn, the Fanonian mandate by Mr. B.: to discover our mission and either fulfill or betray. It was the mid-aughts when I was first part of those conversations and the world was rapidly, paradoxically, opening and closing at the same time. We were about to have the power to share truth and possibility on ever-expanding platforms, reaching people we would likely never have the chance to meet—and reach them all at once! We didn’t have to ask someone to grant us an audience. We could create our own audiences—if we used our imaginations well.

Harry Belafonte chose us. Us being the generations behind him. Us being people from all stations in life.

And if we could do that, we could make the sort of changes that were needed in the pursuit of justice and dignity for all. If we chose love, as my friend Errol would say, as a demonstration, not simply as a proclamation, we could win. For our part, especially for those of us in media, we knew how seismic the shift that was coming would be. We talked about it. Talked about what we could do and then suddenly the day was here and faster than you could Venmo someone a little cash, a whole lot of us seemed to trade in speaking truth, for speaking something closer to truth-adjacent. Better for likes, the followers, the illusion of influence.

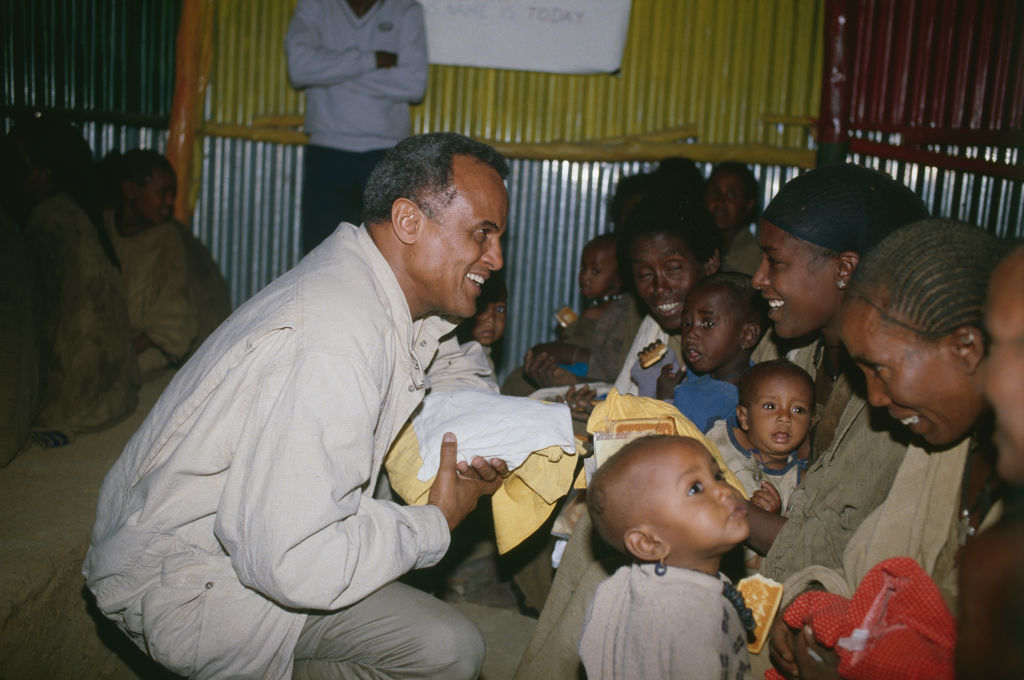

Harry Belafonte participates in the distribution of food to refugees in Ethiopia on June 13, 1985. | Source: William Campbell / Getty

And no matter how big we’d imagined the change was going to be, I don’t know that we predicted that a whole bunch of us would swap out strategies for social justice with strategies for social climbing. We didn’t predict how well we could talk about love, but not have the actual courage to do the hard work of love, the very thing that was needed when the white supremacists from the right and the left came for one of us. We needed to love truth, and justice, and others so deeply in those moments and often we did not. Often, we were silent. Across all those platforms. And again and again and again in that terrible silence, I watched some of our brightest stars disappear overnight. The trucks that had always come for people who told the truth, still came, but now they came more stealth, shielded almost entirely by NDAs in this new world of corporatized social justice work, corporatized pro-Blackness.

Despite access to resources and platforms and opportunities that generations before us could not imagine, some of the hardest working and most committed of people were tossed aside by rumors and outright lies, driven out, disparaged and discarded, Robeson-like. And I’ve watched, to my horror, how those who could have stopped it just by speaking up, decided to instead shut up. After, all that could be heard was the shattering of hearts, of lives, of vision—along with the sound and fury that is the character of short-game plays. The ones where the dividends come in just as immediately as they evaporate. And the cost of those choices has been all of the disappeared brilliance and all of the dead, now behind us, the young ones taken from us out of season, the ones a little older and still alive, but barely, gasping for air as it runs out of the coffins that whispering campaigns, lies and innuendo create.

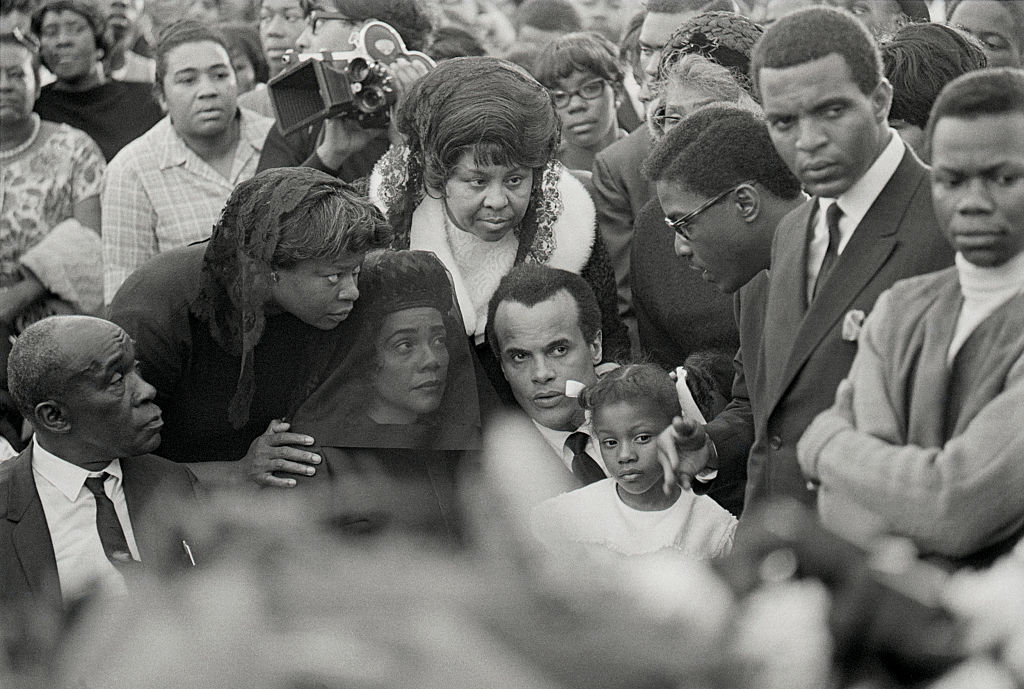

Coretta Scott King sits surrounded by family on April 9, 1968, at the funeral of her husband, Martin Luther King, Jr. who was assassinated as he stood on the balcony of a Memphis motel. Harry Belafonte sits beside her. | Source: Bettmann / Getty

The Legacy

I’m supposed to be writing a tribute to Harry Belafonte. And I could write about all the ways he moved me, moved my daughter, all those moments of wisdom he shared over the 20 years I knew him. I definitely wanted to say that once he called me beautiful, but that didn’t really have a place in this narrative except for me wanting to insert it because when Harry Belafonte calls you beautiful, somehow you really felt it, even someone as insecure as me. I really felt it. He made me feel beautiful. He made us feel beautiful. And that does matter.

I’m trying to say that tributing Mr. B. is less about anything I could ever write than it is about all the ways that I—that any of us—can choose to live. It’s about what we do even when we’re scared and even when NDAs are on the table. It’s about what we do and say when the people who are harming us are the very people who are supposed to be on our side, and telling the truth feels scary because those are the people who seem to have something we believe we need. A job. A grant. An opportunity. A moment of grace. But unless and until those things are shared with pure intention, the freedom we really need, will remain forever out of our reach.

The only way to truly tribute Mr. B is for us to be as fiercely and fearlessly honest as he was, as critically thinking and as compassionate and humble as he was.

Over the course of 20 years, I saw Mr. B give all that we need—jobs, grants, opportunities and grace—to people freely, with pure intention. I saw him give to people he knew and people he didn’t know. I saw him give to people who were well-known and to people whose names I’ve lost to time. What directed Mr. B.’s giving was that he saw a chance to bend the arc, the opportunity to ensure accuracy in the telling, a moment to demonstrate in real time, the courageous work of love.

Harry Belafonte and his wife, Pamela Belafonte, are shown at The Apollo Theater on November 9, 2015, in New York City. | Source: Johnny Nunez / Getty

That was Harry Belafonte. That was Mr. B. That was why I loved him so.

And that is why the only way to truly tribute him is for us to be as fiercely and fearlessly honest as he was, as critically thinking as he was, as compassionate and humble as he was. As just as he was. And to choose that character every chance we get and in every place we find ourselves. In offices. In movements. In schools.

Or

down at that market where you can hear

the ladies cry out while on their heads they bear;

and the ackee, rice, saltfish are nice,

and the rum is fine any time of year.

Farewell, Mr. B.

My Jamaica.

Farewell.

asha bandele is a multiple award-winning New York Times best-selling author and journalist.

SEE ALSO:

Harry Belafonte Blended Music And Politics To Make Lasting Social Change

Tributes Pour In For Harry Belafonte After Legendary Actor And Activist Dies At 96