Coke Rap: A Soundtrack Of Survival For Middle-Aged Black Men

It’s Clipse Day: Coke Rap, Middle-Aged Black Manhood, And The Soundtrack Of Survival

Let the Church say “Yugh!”

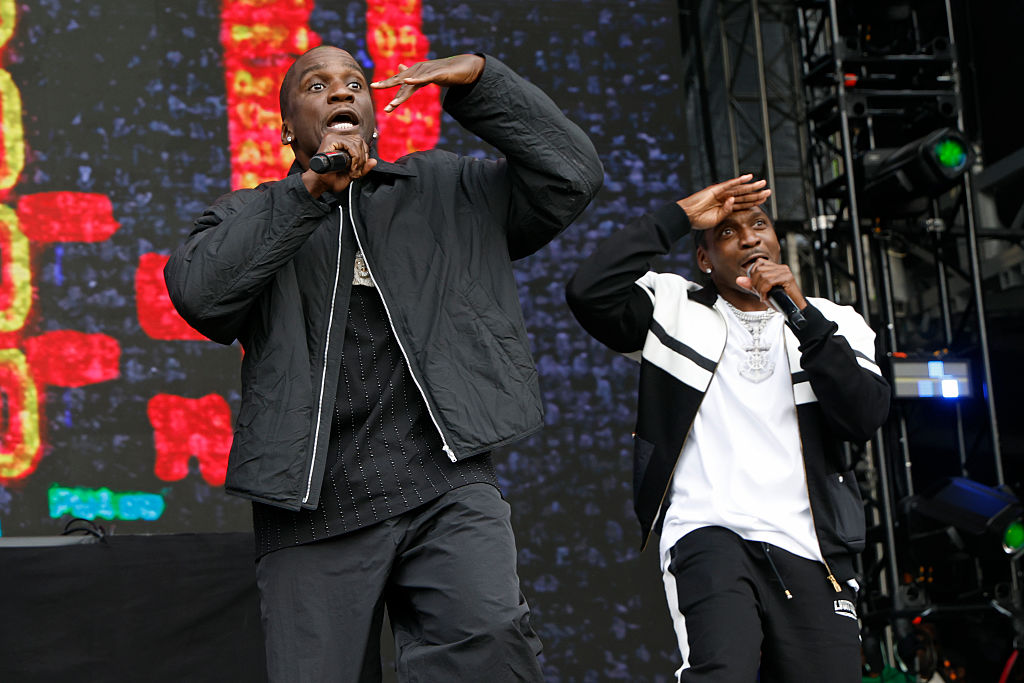

Friday, July 11, marks the drop of Let God Sort Em Out, the long-awaited new album from Clipse, our favorite brotherly rap duo from Virginia Beach (757 REPRESENT!) and the undisputed pen-wielding philosophers of powdery prosperity.

To be clear, this is not just some album release. For Black men over 40, this is our Cowboy Carter. It’s our Renaissance. This is the moment we’ve been holding out for now for over a decade. It’s our opportunity to feel understood, heard, and maybe even redeemed through 16 tracks of elegantly constructed street soliloquies about things we may or may not have done, dreamed about doing, or simply watched happen from the safety of a front stoop or bedroom window.

And while your preferred music streaming platform is probably pushing you toward songs made for TikTok dances, wedding montages, or inspirational gym reels, Coke Rap isn’t interested in choreography or virality. It’s about narrative. It’s about memory. It’s about survival. And nobody does that better than Clipse.

Before we go any further, what is “Coke Rap,” exactly?

For the uninitiated, Coke Rap is not just a subgenre; it’s a cinematic universe. It’s rap music that explores the hustle, the high-stakes calculus of street life, and the gritty poetry of the drug game with nuance, complexity, and a certain… aspirational gloss.

It’s the hip-hop equivalent of a Scorsese film. If trap music is modern blues from the street corner, Coke Rap is the game in an opera. It’s layered, introspective, and meticulously detailed. Think less “I got bricks in the trunk” and more “In 2004, I wore a white mink in front of customs and didn’t flinch.”

It’s what happens when drug dealing becomes art, filtered through metaphor, confession, and craftsmanship. It’s elevated storytelling, not just a glamorized justification for poor decision-making.

But we have to start with the blueprint: Raekwon and the Purple Tape…

We can’t talk Coke Rap without invoking the godfather: Raekwon the Chef. When he dropped Only Built 4 Cuban Linx… in 1995 (IYKYK, “The Purple Tape”), it changed the game.

Up until then, drug rap had been raw, cautionary, and aggressive, designed to either scare you straight or make you think twice. Think Kool G. Rap, “Road To The Riches” or Ice T’s, “High Rollers.” But Rae took it in a new direction. He made it stylish. He gave it structure. He gave it a vocabulary shaped by a milieu.

Cuban Linx played like a rap epic: Ghostface was the co-star, RZA did the score, and Rae was both the narrator and protagonist. It wasn’t about glorifying the game; it was about creating a space to imagine what it could have looked like if it wasn’t rigged and the players actually won. All interspersed with lines from Scarface and Kung Fu dubs, punctuating the action.

He laid the foundation for The Lox, Beanie Sigel, and Cam’ron. Later came Freddie Gibbs, Benny the Butcher, and Boldy James. Each added their own ingredients to the pot. But it was Clipse who turned the Pyrex into a fine dining experience.

When “Grindin’” dropped in 2002, it didn’t sound like anything else. The beat felt like Neptunes-made Morse code banged out on a high school cafeteria table. Pusha T and Malice didn’t just rap, they reported. It challenged you to ignore it.

Where others yelled, they spoke in monotones. Where others flexed, they measured. And where others sold a lifestyle, they sold the consequences.

Clipse wasn’t just narrating the hustle; they were theologians of it. They explored the paradox of ambition, the thin line between survival and sin. They opined on the way America criminalizes your options, then punishes your outcomes. And they did it all while balancing tall tees with couture and referencing obscure French champagne vintages.

To put it plainly: Jay-Z sold drugs and told you about it as an outsider. Clipse sold drugs and made you feel like you were in the backseat of a 1992 Acura Legend on 18-inch Hammers while it was happening.

And now, with Let God Sort Em Out, they’re back. Not just to remind us how sharp their bars are, but to remind us of a genre, a generation, and a geography of memory that needs revisiting.

Because if you’re a middle-aged Black man, this is a cultural touchstone.

To understand the appeal of Coke Rap, you have to understand what the War on Drugs and the Crack Era did to Black communities, and Black boys of that generation in particular.

We came of age during a time when the war on drugs was a war on us. When the heroes on TV didn’t look like us, and the so-called villains all too often resembled people who lived down the block. When the future felt uncertain, and options felt compartmentalized.

Coke Rap gives us the ability to reimagine that past. To take those dusty corners and broken dreams and repurpose them into art, mythology, and, dare I say, self-esteem.

It’s not about glorification. It’s about reclamation.

White men have had the Western for over a century, where they got to shoot first, rewrite history, and ride off into the sunset as heroes, no matter how messy their morals were. Conquest and extermination were sanitized and glamorized. People who actively participated in very bad things got to be presented as very good guys, their villainy obscured by rewritten valor. The ethnic cleansing of America was reimagined as a folk tale.

Coke Rap is our Western. But instead of horses and stagecoaches, it’s Crown Vics and Mazda MPVs. Instead of saloons, it’s corner stores. Instead of striking gold, it’s reaching a key. Everybody gets away with it. Nobody gets shot. Nobody goes to prison. And we all live full and happy lives without ever worrying about the cops.

Through Coke Rap, we get to become the protagonists of our stories, not cautionary tales, not supporting characters. Not stereotypes, tropes, or one-dimensional caricatures of people society thought deserved to be stopped and frisked.

Just complicated men undergoing complicated situations, trying to make it and make it make sense.

Let me be clear: this music hits different when you know people. When the lyrics feel like they could’ve been your cousin’s diary or your brother’s confession, the proximity gives it its power.

We all knew a dude who was smart enough to be a lawyer but hit the corner instead. Not because he was a bad person, but because he was raised in a place where law school didn’t feel like an option. His reach was limited by a narrow vision created by a Reagan era that was obsessed with the wealth of a few, predicated on eliminating opportunities for the many.

Coke Rap doesn’t ignore that complexity. It lives in it. It’s steeped in that uncomfortable reality. It doesn’t hide from the disgusting irony that their success could only happen via the destruction of others.

It says: “You might not have liked my choices, but you’re gonna respect the calculus.” It invites empathy, not for the crime, but for the conditions. Nobody’s hands are clean and all the participants are equal parts predator and prey.

And that’s why this album resonates so much in this particular moment.

The Trump Era and the Reagan days don’t feel so different.

I mean, our perspectives have changed with time, but the conditions persist.

Sure, we’re in our 40s now. We’re raising kids. We’re managing blood pressure. We’ve switched from Crown Royal to red wine and started looking at how much sugar is in that jar of spaghetti sauce (hint: A LOT).

But that doesn’t mean we forgot.

Let God Sort Em Out arrives like a time capsule. It reminds us that we made it through. That we were there. Even when confronted by this modern iteration, we’re genetically predisposed to survive. And that our stories matter.

And unlike TikTok songs designed for 30-second dances, Clipse gives us compositions that breathe. That sit with you. That grow with age.

When Push speaks on family.

When Malice speaks on faith.

This album isn’t for the charts, it’s for the barbershop convos, the solo car rides, the late-night recitations as a proverb to a younger guy who needs some guidance. It’s for that moment when you catch a line so good it makes you pause the track and shake your head in disbelief, and then contemplate how that relates to your divorce or your relationship with your children.

We was there. And now, we here.

Some men listen to classic rock. Some rewatch The Sopranos on repeat. We play Coke Rap.

We remember who we were, who we could’ve been, and how close some of us came to not being here at all. The soundtrack helps us process that. It gives us space to mourn, to marvel, and to move forward.

We weren’t supposed to make it. But we did. And now, after such a long pause, we get to ride out to grown-man music that respects that journey again.

So yes, it’s Clipse Day. And yes, the album is called Let God Sort Em Out. But what it really represents is this: our chance to reclaim the stories we lived through with dignity, humor, and lyrical precision.

Because if America gets to mythologize cowboys and Confederates, we get to celebrate the men who made it out the other side of our national nightmare, and did so with punchlines, Prada, and just enough pain to make it stick.

Merry Clipsemas, fellas!

Corey Richardson is originally from Newport News, Va., and currently lives in Chicago, Ill. Ad guy by trade, Dad guy in life, and grilled meat enthusiast, Corey spends his time crafting words, cheering on beleaguered Washington DC sports franchises, and yelling obscenities at himself on golf courses. As the founder of The Instigation Department, you can follow him on Substack to keep up with his work.

SEE ALSO: