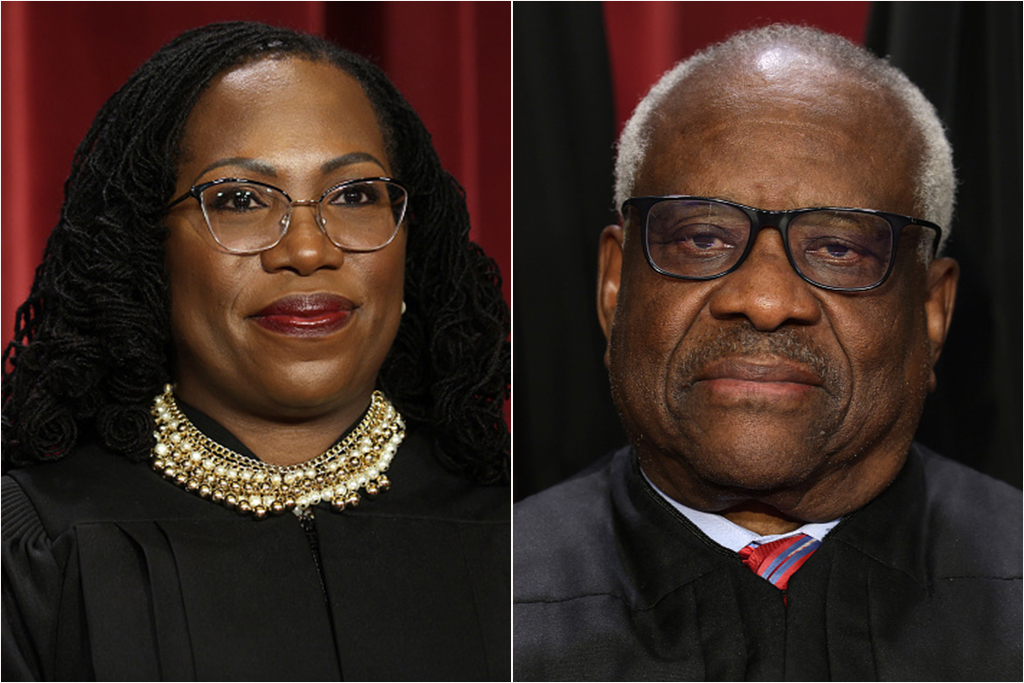

Affirmative Action: Ketanji Brown Jackson vs Clarence Thomas

Ending Affirmative Action: Ketanji Brown Jackson’s Dissent vs. Clarence Thomas’ Concurring Opinion

Source: Getty Images / Getty

In the aftermath of the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision Thursday to end affirmative action at two prominent universities in a ruling that is expected to set a national precedent on considering race for college admissions, the only two Black judges in the conservative-leaning body offered opinions that couldn’t be more different.

The court ruled in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard and UNC that colleges and universities “may never use race as a stereotype or negative, and — at some point — they must end.”

It was in that context that Associate Justice Clarence Thomas readily concurred with the court’s opinion. Just weeks after Thomas dissented with a Supreme Court ruling that upheld voting rights for Black people in Alabama, he admonished the court’s “failure” and “mistake” with Grutter v. Bollinger, which in 2003 agreed that considering race in college admissions did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause.

Thomas’ concurred with the decision in spite of his open acknowledgment of “the social and economic ravages which have befallen my race and all who suffer discrimination.”

Read Thomas’ full dissent below:

The great failure of this country was slavery and its progeny. And, the tragic failure of this Court was its misinterpretation of the Reconstruction Amendments, as Justice Harlan predicted in Plessy. We should not repeat this mistake merely because we think, as our predecessors thought, that the present arrangements are superior to the Constitution. The Court’s opinion rightly makes clear that Grutter is, for all intents and purposes, overruled. And, it sees the universities’ admissions policies for what they are: rudderless, race-based preferences designed to ensure a particular racial mix in their entering classes. Those policies fly in the face of our colorblind Constitution and our Nation’s equality ideal. In short, they are plainly—and boldly—unconstitutional. See Brown II, 349 U. S., at 298 (noting that the Brown case one year earlier had “declare[d] the fundamental principle that racial discrimination in public education is unconstitutional”). While I am painfully aware of the social and economic ravages which have befallen my race and all who suffer discrimination, I hold out enduring hope that this country will live up to its principles so clearly enunciated in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States: that all men are created equal, are equal citizens, and must be treated equally before the law.

Thomas’ opinion stands in stark contrast to the dissent from Brown Jackson, who wrote that her conservative-leaning Supreme Court colleagues were displaying a “let-them-eat cake obliviousness” and accurately pointed out that just because they were “deeming race irrelevant in law does not make it so in life.”

Brown Jackson later added: “Although formal racelinked legal barriers are gone, race still matters to the lived experiences of all Americans in innumerable ways, and today’s ruling makes things worse, not better. The best that can be said of the majority’s perspective is that it proceeds (ostrich-like) from the hope that preventing consideration of race will end racism. But if that is its motivation, the majority proceeds in vain. If the colleges of this country are required to ignore a thing that matters, it will not just go away. It will take longer for racism to leave us. And, ultimately, ignoring race just makes it matter more.”

Read the full Supreme Court decision, including Thomas’ concurring and Brown Jackson’s dissent, by clicking here.

SEE ALSO:

A Brief History Of Affirmative Action In America

Majority Of Americans Believe College Should Consider Race In Admissions, Poll Finds