Black Engineer Creates Technology To Help Dark-Skinned Patients

Black Engineer Develops New Technology To Benefit Dark Skinned Patients

Source: mr.suphachai praserdumrongchai / Getty

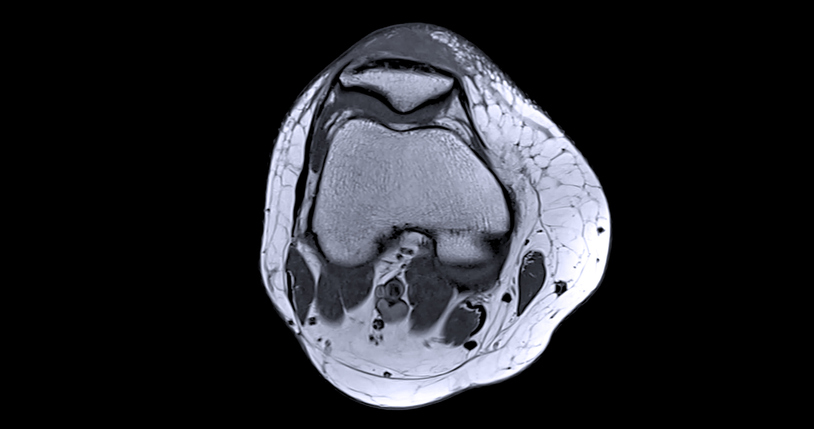

Dr. Muyinatu “Bisi” Bell, a Black associate professor at Johns Hopkins University, has discovered a new way to deliver clear imaging pictures for patients with darker skin tones. According to a press release, Bell and her team at Johns Hopkins created a new algorithm that can support photoacoustic imaging that combines ultrasound and light waves to render images on people with darker skin tones.

The new algorithm helps to filter light during the imaging process. It also gives healthcare experts a better picture of arteries and internal structures that may be hard to see in people of darker skin tones.

Muyinatu Bell and her associates conducted several experiments and found that the amazing technique produced “shaper images” for people of darker hues.

“When you’re imaging through skin with light, it’s kind of like the elephant in the room that there are important biases and challenges for people with darker skin compared to those with lighter skin tones,” said Bell, who is an associate professor of the John C. Malone Electrical and Computer Engineering, Biomedical Engineering, and Computer Science at Johns Hopkins.

“Our work demonstrates that equitable imaging technology is possible.”

During the imaging process, when light hits tissue in the body, it creates a sound wave that ultrasound machines use to produce clear images of arteries, blood, and other internal organs. However, the process has not been easy for people with darker skin tones because melanin absorbs more light— which can impact the signal to render a clear image.

Muyinatu Bell and the team’s new technique helps to filter out excessive light, which leads to a better signal for rendering clear images.

False imaging can lead to life-threatening consequences.

A 2020 study conducted by The New England Journal of Medicine found that Black patients were three times more likely to have low oxygen levels go undetected during a pulse oximetry reading than white patients.

Pulse oximeters are non-invasive medical devices used to measure oxygen levels in the blood, but evidence has shown that they don’t work well on people with darker skin, as melanin can block the absorption of light needed for the machine to accurately measure oxygenated blood in a patient’s finger. Many of those impacted were less likely to receive supplemental oxygen during their hospital stay, a subsequent study found.

Part of the study was conducted during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“There were patients with darker skin tones who were basically being sent home to die because the sensor wasn’t calibrated toward their skin tone,” Bell said of the heartbreaking study.

Thanks to the new algorithm, the Johns Hopkins team is now working on a way to use their technique for breast cancer imaging and surgical navigation for medical diagnosis, according to the release.

“We’re aiming to mitigate, and ideally eliminate, bias in imaging technologies by considering a wider diversity of people, whether it’s skin tones, breast densities, body mass indexes—these are currently outliers for standard imaging techniques,” Bell added.

“Our goal is to maximize the capabilities of our imaging systems for a wider range of our patient population.”

SEE ALSO:

The Brains Of People With Alzheimer’s Disease: Researchers Zero In On Understanding What Goes Awry

Courageous Journeys: Black Women’s Resilience On The Path To Wellness