The Untold Story Of The Black Pilgrims Of Plymouth Colony

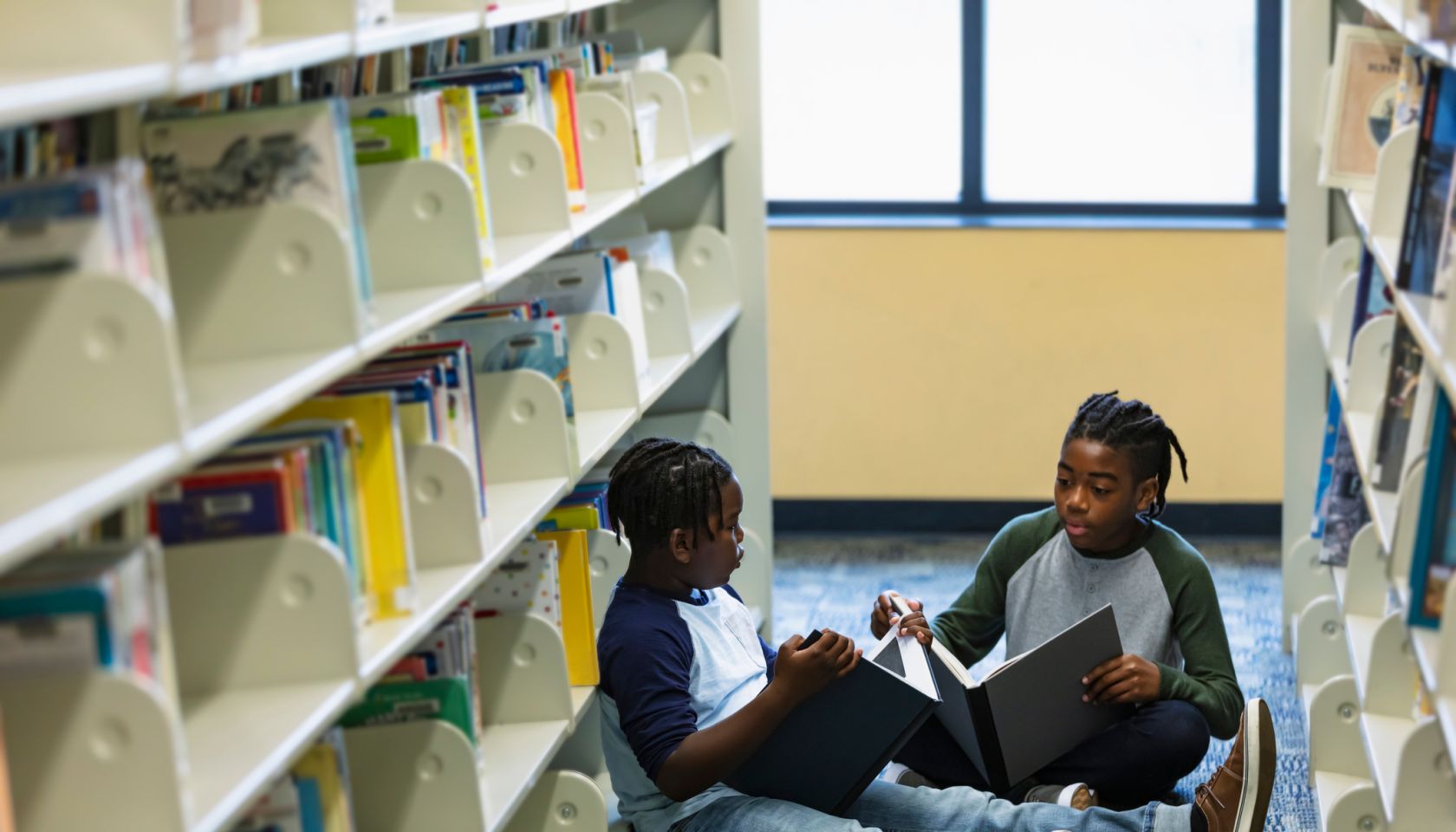

Source: Boston Globe / Getty

UPDATED: 10 a.m. ET, Nov. 26, 2024

Let’s have a serious conversation about Black pilgrims. Were there actually Black pilgrims eating with white pilgrim settlers in the 1600s? The short answer is yes and not all of them were slaves.

In the tapestry of American history, the narratives surrounding Black pilgrims are often hidden deep inside the crevasses of time, waiting to be unfurled. From the early days of colonization, Black people have been interwoven into the fabric of this nation, shaping its cultural, social and even religious landscape.

MORE: The Brothers Of Pine Oak: The Mysterious Disappearance Of A Slave Family Searching For Freedom

Join us as we navigate the hallways of history, uncovering the challenges, triumphs and enduring legacies of our remarkable ancestors.

In this episode of Black Folklore, we unpack the rarely-told story of the Black pilgrims of Plymouth, who, against all odds, sought spiritual fulfillment, freedom and a place in the ever-evolving tapestry of the American dream.

For a long time in American history, the Black pilgrim was just a myth. It wasn’t until 1981 that historians started to believe that Black people were indeed a part of American life in the mid-1600s.

(This isn’t a piece on the history of the pilgrims. So if you’re looking for that, you are in the wrong place. But, this might help. Click here.)

In 1981, historians announced that they had found evidence that an early pilgrim settler was of African descent. According to the Washington Post, the man’s name was included in a 1643 record listing the names of men able to serve in the Plymouth, Mass., militia. The man was identified as “Abraham Pearse, blackamore.”

During the early stages of America, Black people were often called blackamore, which is a derivative of “black Moor.” The term was used to describe a person with darker skin. The Moors had a history with the Europeans and often worked as servants or enslaved people.

Some historians believe that Pearse came to Plymouth as an indentured servant, but others claim he was never enslaved and that he voted and owned land after arriving in Plymouth in 1623.

After years of research, a DNA analysis continued to make this tale even more alluring. In 2011, Brad Pierce, a radiologist from Little Rock, reviewed DNA tests of descendants of Abraham Pearse and found that Pearse’s father was not of African descent, further adding speculation to Abraham Pearse’s story, although the tests never proved if Pearse’s mother was white or Black.

This left researchers wondering who was actually the blackamore listed in the 1643 militia document.

Eugene Aubrey Stratton, a former historian general of the General Society of Mayflower Descendants, claimed that the blackamore listed could have been a man named Hercules.

Source: Boston Globe / Getty

During the early Americas, Africans were given English names by settlers looking to make sure Black people knew their place in Puritan society.

According to the Washington Post, Hercules was first mentioned on “5 March, 1643/64,” in a court record from a case to decide how long Hercules, who was an indentured servant, should serve a man named William Hatch.

Stratton also claims that some evidence proves there was another black man whom Pilgrims considered a “transient in Plymouth Colony” as early as 1622.

“There was a man named John Pedro, who was also identified in records as John Pedro a Neger and aged 30 who arrived on a ship called the Swan in 1623,” wrote Stratton in his book Plymouth Colony: Its History and People, 1620-1691.

Stratton also said that finding out how many Blacks were in Plymouth was nearly impossible because they only showed up on records when there was legal trouble.

“It is not possible to tell how many blacks might have been in Plymouth Colony, for they would usually appear in records only when involved in some kind of legal situation,” Stratton wrote. “But gradually it can be seen that the black population was growing.”

Stratton’s research also unearthed a Black female maid who in 1953, accused a white man of “receiving tobacco and other things of her which were her masters,” as well as a 1676 Black man named Jethro who was captured by Native Americans, then “retaken by colonists and ordered to serve successors of his deceased master for two years” before being freed.

Slavery definitely occurred among early pilgrim settlers, but it looked slightly different than it did in other European settlements during early America.

Source: Robert Holmes / Getty

According to Cape Cod Times, Black people who lived in the Plymouth Colony from 1623-1692 were categorized into three groups by pilgrim settlers. They were either freemen, bonded or indentured, or slaves. The Black people who were fortunate enough to attain freeman status were lucky but still did not have the same rights as white freemen. Black freemen were rarely allowed to vote or own land. By 1715, there were more than 2,000 enslaved people in Massachusetts

Because the pilgrims were such a religious people, slavery looked a little different than it did in other European settlements in early America.

Slave owners were generally wealthy merchants with connections to larger slave trading communities such as Boston and Newport. The majority of white pilgrims couldn’t afford slaves so the institution of slavery never maintained a foothold. This allowed Black pilgrims to integrate into pilgrim society, serving in Plymouth County’s militia, helping maintain the Pilgrim Protestant Congregational church, and aiding in the economic success of the Plymouth Colony.

There is no doubt that Black pilgrims existed during the early stages of America, but their stories are rarely told. By casing a spotlight on these overlooked narratives, we can have a more inclusive and accurate understanding of American history. And as we stand at the intersections of past and present, let us learn from the lessons of our ancestors. The tales of Black pilgrims serve as a reminder that Black history is also American history.

SEE ALSO:

The Day Black Boys Burned: Uncovering The 1959 Fire At The Negro Boys Industrial School

The Incredible Henry ‘Box’ Brown: This Black Man Mailed Himself To Pennsylvania To Escape Slavery