Transracial Adoption: West Virginia Case Spotlights Black Children

White Couple Accused Of Enslaving Adopted Black Children Draws Attention To Transracial Adoptions

The topic of transracial adoptions is in the spotlight after a white couple in West Virginia was charged with enslaving the Black children they adopted and locking them in a barn, among other alleged offenses.

Defined as the adoption of a child that is of a different race than the adoptive parent(s), transracial adoption has surged in apparent popularity in recent years. However, as evidenced by the recent allegations out of West Virginia, transracial adoptions may not always be initiated with the sincerest of intentions.

MORE: Foster Care: Why Are Black Children Overrepresented In Child Welfare?

Transracial adoption in West Virginia

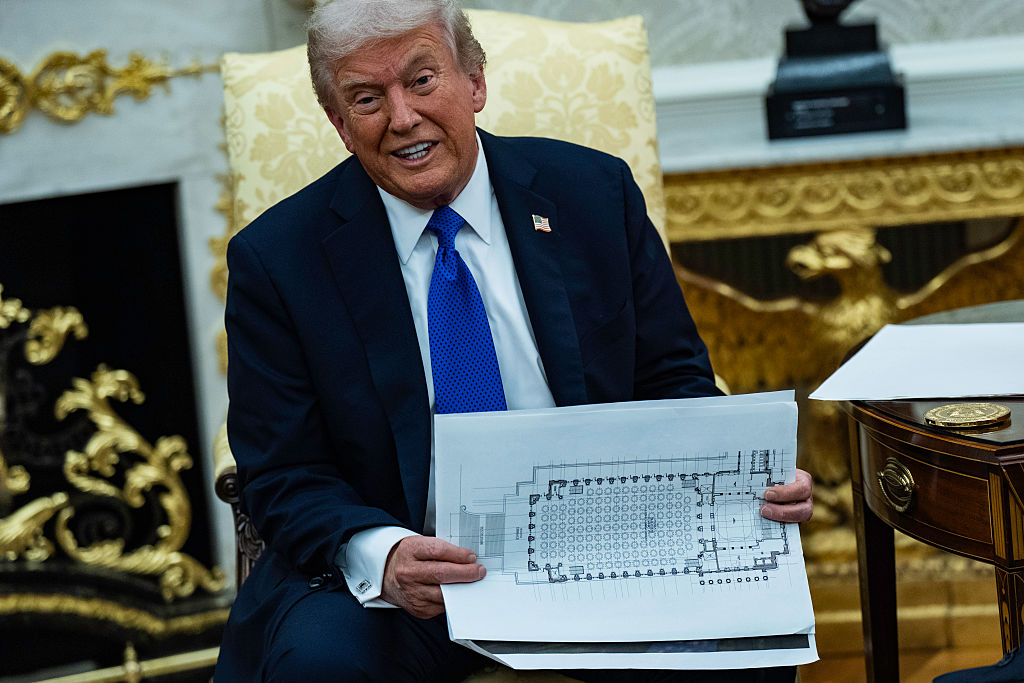

In case you missed it, Donald Ray Lantz and Jeanne Kay Whitefeather of Sissonville, West Virginia, stand accused of locking their adopted Black children in a barn and forcing them into slave labor.

Lantz and Whitefeather were initially arrested last October “after a wellness check led to the discovery of two of the couple’s five adopted children living in deplorable conditions locked in a shed on the Sissonville property on Cheyanne Lane,” according to WV Metro News.

Their bond was set at $200,000 each, which they were able to post, but, on Tuesday, Kanawha County Circuit Judge Maryclaire Akers revoked that bond and more than doubled the amount in light of numerous additional charges alleging a myriad of abuses committed against all five of their Black children, ages 6, 9, 11, 14 and 16. The couple’s bond is now set at $500,000 each. Both Lantz and Whitefeather pleaded not guilty to a slew of damning charges, including human trafficking of a minor child, use of a minor child in forced labor, and child neglect creating substantial risk of serious bodily injury or death.

Transracial adoption statistics

According to data from the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, which advises the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), transracial adoptions have “outpaced the growth in same race adoptions. Between 2005-2007 and 2017-2019, the number of transracial adoptions increased by 58% while the number of same-race adoptions increased by 24%. Transracial adoptions grew by 5 points, from 23% to 28% of all adoptions.”

When broken down along specific racial lines, the research also found that “The increase in proportion of transracial adoptions of Black children was mostly because of a decline in same race adoptions.”

A report on transracial adoptions published by the University of Nevada, Reno, noted that some private adoptions allow adoptive parents to select the race of the children they want to adopt. In fact, white parents who adopt Black children are among the most “common transracial adoptions.” That is particularly true with international adoptions.

It’s a practice with which the National Association of Black Social Workers has long taken issue, citing physical, psychological and cultural concerns.

Historically, Black children have long been racially overrepresented in foster care. Because of that, legislators enacted a law – The Multiethnic Placement Act of 1994 – that bans “delaying or denying foster or adoptive placements because of a child or prospective foster or adoptive parent’s race, color or national origin and from using those factors as a basis for denying approval of a potential foster or adoptive parent. The law also requires agencies to recruit foster and adoptive parents that reflect the racial and ethnic diversity of children in out of home care, a process known as diligent recruitment.”

But as shown in West Virginia, and other places, transracial adoptions aren’t always altruistic.

Transracial adoptions’ financial implications

That truth was also on display a few years ago with the story of Devonte Hart, a Black boy who was killed alongside his five siblings when their adoptive white parents drove their SUV off a cliff in Northern California in 2018.

Devonte, 16, was known for a viral photo in which he hugged a police officer at a racial justice protest in 2014.

In addition to Devonte and his siblings – Markis Hart, 19; Jeremiah Hart, 14; and Abigail Hart, 14 – the Harts were able to adopt three more children even after Minnesota police questioned them about child abuse.

It’s unclear why the adoptive parents – Jennifer and Sarah Hart, both 39 – adopted the Black children from Houston, Texas, which is more than 1,200 miles from their home in Alexandria, Minnesota. However, reports suggested the women made a hefty profit from adopting the Black children.

The San Antonio Express-News reported at the time that the adoptive parents “likely received more than $270,000 from the state of Texas to help care for the children” and the state “paid a Jennifer Jean Hart monthly adoption subsidies for her children over the past decade. Hart got nearly $1,900 each month, most recently in March.” The outlet added: “Most families who adopt children out of foster care from Texas get monthly payments that range from $400 to $545 per child to help cover care costs until the child turns 18.”

More recently, drama exploded between former NFL offensive lineman Michael Oher – whose life story was depicted in the Oscar-winning film The Blind Side – and his adoptive white parents, Sean and Leigh Anne Tuohy, who took him in as a teenager. Nearly 20 years later, Oher said the Tuohys misled him into entering a conservatorship and signing away his legal rights. That led to an ugly exchange of accusations last year with financial implications.

Black children adopted by white parents

According to VeryWellFamily, Black children are twice as likely to enter the foster care system as white children and remain in the system for about nine months longer on average.

Agencies also struggle with placing Black children with Black foster parents due to disparities in Black families trying to adopt.

“[In] the child welfare system they often don’t have enough families who are willing to adopt, [and] they don’t have enough families who are willing to adopt the children who are actually available for adoption,” Susan Dusza Guerra Leksander, the clinical director at PACT, An Adoption Alliance, told VeryWellFamily.

And while families of other races do adopt Black children, they often struggle to help the child navigate the unforgiving experience of growing up Black in America.

“[W]hite (or other race) adoptive/foster parents can’t teach their adoptive/foster children the Black experience the same way as or as well as a Black parent could,” Aaron Johnson, founder and president of WAT! Black Family Adoption Assistance, Inc., told VeryWellFamily. “Sure, they can read books or blogs and get by well enough, but they won’t ever be able to teach (or relate to) the Black experience as well as someone who has lived it.”

SEE ALSO:

White Man Allegedly Calls Adopted Black Daughter The N-Word In Viral Social Media Thread

‘I Want My Son To Be Safe’: Sandra Bullock Opens Up About Raising A Black Child

[ione_media_gallery id=”4678208″ overlay=”true”]