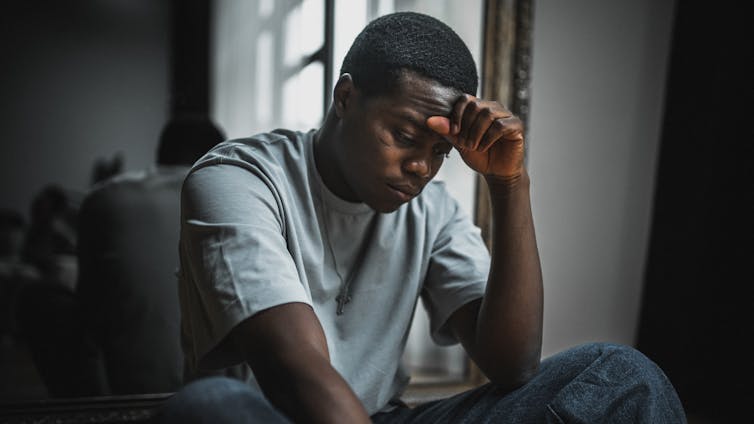

The Lingering Mental Health Impact Of Prison On Black Men

Mike returned home to Philadelphia after a 15-year prison sentence and suffered an emotional breakdown.

“I just couldn’t stop crying … I don’t know. It was the anxiety. It was just a lot,” he said. “I was under a lot of pressure and it just came crashing down.”

Mike, who was in his late 40s when we spoke, told me about his childhood filled with abuse, his first arrest at age 14, and the over 20 years of his life that he spent behind bars.

As a registered nurse and nurse scientist who studies how incarceration affects mental health, I know Mike’s experience after release from prison is not uncommon. Studies show that Black men who have experienced incarceration have higher rates of PTSD, depression and psychological distress compared with Black men who have never been incarcerated.

Working in psychiatric hospitals in Philadelphia, I met many patients in crisis who had been incarcerated at some point in their lives. As a part of my doctoral research, funded by the National Institute of Nursing Research, I interviewed 29 formerly incarcerated Black men to understand how incarceration has affected their mental health.

My peer-reviewed findings were published in the journal Social Science & Medicine. All quotes shared here use pseudonyms to protect the men’s privacy.

Trauma of incarceration

Mass incarceration in the U.S. has serious health consequences for individuals, families and communities. In Philadelphia alone, over 20,000 people return home from incarceration each year.

While incarceration rates are declining in Philadelphia, the needs of those coming home remain significant.

Many formerly incarcerated men described experiencing or witnessing violence, including being beaten by correctional officers and witnessing close friends get assaulted or killed.

“You know you are not regular because you come from a traumatic situation, right?” said Thomas, 44, who spent 18 years incarcerated.

The participants expressed that racism was common, especially while incarcerated in facilities located in the rural central and northern regions of Pennsylvania.

“I ain’t gonna sugar coat it – Black people going up into them white people mountains, they call you [N-word] all day long and you basically there to accept it,” Antonio told me.

Incarceration was especially difficult for those who were held for months pretrial without ever being convicted and those incarcerated during COVID restrictions who spent more than 23 hours a day in their cells.

‘Even though I’m free, I ain’t free’

Participants described life on parole or probation, or in transitional housing, as another form of confinement.

Ken, 56, has been out of prison for over a decade but said, “I’m still locked up, even though I’m free, I ain’t free. You just get a whole new set of rules and regulations.”

Men described significant anxiety related to community supervision requirements, including difficulty sleeping the night before a probation appointment.

Participants also described distress caused by “no association” restrictions. These are common parole and probation requirements that prohibit people under supervision from interacting with others who have criminal records, are also under supervision or are currently incarcerated. Violating this requirement can lead to a technical violation and reincarceration.

While these requirements are meant to reduce the risk of reoffending, they often isolate people from supportive relationships and resources, including housing and employment.

“[There are] a lot of smart brothers in there. And it hurts my heart. And that’s where the depression coming in too,” said Reese, who spent six years incarcerated. “I can’t contact them in jail. … That’s just how it is in the system.”

Philadelphia has the highest rate of community supervision – including probation and parole – among the largest U.S. cities, according to a 2019 analysis by The Philadelphia Inquirer.

At that time, the Inquirer reports, 1 in 23 adults in Philadelphia were under community supervision – and 1 in 14 Black adults in Philadelphia.

The men I interviewed said they felt like parts of them never left jail or prison, while others felt that they brought prison or jail home with them.

Tyrese, 34, said he stays home as often as he can.

“I’ve been out of the joint for seven years now and feel like I’m still institutionalized, I guess,” he said. “I know people that don’t even come outside,” referring to other formerly incarcerated men.

Others had dreams that they were back in a cell, or at home still wearing jail clothing. Long after release, many described constant hypervigilance and anxiety.

“I can be walking to the bus station and there be people walking around me, I’m constantly watching them,” said Anthony, who was first incarcerated at age 18 and served 16 years. “I’m watching every movement they’re doing. That’s a habit I had from jail.”

Finding work

People who have been incarcerated often struggle to find employment after release, as many employers are unwilling to hire a person with a criminal record.

This leaves about 35% of formerly incarcerated Black men unemployed.

At the time of our interview, Tay, 31, was working part-time in carpentry. “Because I had felonies on my record a lot of places won’t hire me,” he said. “And a couple of places that I was working with, they ended up firing me once they did the background check.”

These frustrations can easily spill over into family life.

Mark, 30, also works part-time and said he found himself frequently becoming agitated and snapping at his kids, other family members and his girlfriend. “I can’t get the job I want or the job that I need to do what I need to do for my family and I’ll be frustrated,” he shared.

Participants struggled with having to depend on others for basic needs upon release. Kenny, who is now self-employed as a caterer, recalled his experience a few years earlier. “I was crying. I was a grown man, almost 40 years old, and my mother had to buy me underwear, socks,” he said.

The importance of fatherhood

Despite their many hardships, some of the men spoke with joy about reconnecting with their children.

“I think the most positive thing that happened since I’ve been out of prison is I got custody of my sons,” said Ken, a father of two. “Them kids saved me.”

Like many of the other participants with children, however, he was frustrated about being unable to provide for them and worried about repeating harmful cycles.

“You want to do good, but it makes you think bad stuff when you don’t have the right resources,” he continued. “You don’t want [your kids] to do the same things you did.”

Others struggled to bond with their children after years of separation.

John, 29, explained, “The bonding is kind of awkward, because you wasn’t there, especially during the pandemic when there was no visits allowed.”

Returning to disadvantaged neighborhoods

Most people released from incarceration return to neighborhoods with high rates of poverty, violence and other disadvantages.

Shawn, who lives in pubic housing, showed me abandoned buildings and boarded storefronts in his neighborhood and described how the environment made rebuilding his life harder.

For many participants, returning to divested communities brought stress. They experienced frequent exposure to substance use, violence and negative police encounters, and they had limited access to basic resources and job opportunities needed to support recovery and stability.

“This is my real life. It’s not fake. It’s not no, ‘Well, why did he go back and do this or that?’” he said. “I live in an underserved, impoverished, danger zone – period.”

Moving forward

The experiences these men shared with me demonstrate how traumatic incarceration is, even many years after release.

Supporting the mental health of formerly incarcerated Black men requires trauma-informed services, such as culturally responsive counseling, peer support and care that acknowledges the lasting effects of incarceration.

It also means helping them build or rebuild their financial resources, reconnect with their children and loved ones, and supporting the broader communities they return to through investment in housing, employment and accessible health and social services.

Helena Addison, Postdoctoral fellow, Yale University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

SEE ALSO:

The Color Of Health: The Power Of Early Checkups And Why Black Men Shouldn’t Wait To See A Doctor

We Don’t Need Another Podcast: Black Men And The Summer Of Self