Arrest Law Used To Defend White Man Accused Of Killing Ahmaud Arbery

Citizen’s Arrest Law Used To Defend White Man Accused Of Killing Ahmaud Arbery

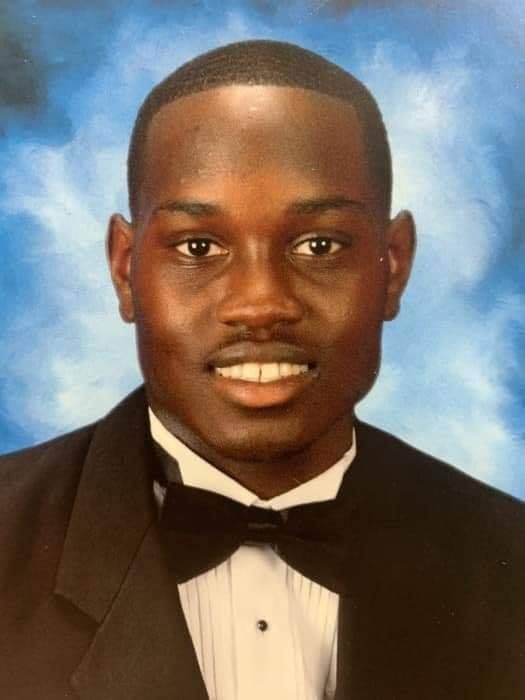

Source: Facebook

Ahmaud Arbery was a 25-year-old former high school footballer who loved to run and stay fit. So it probably came as no surprise when he decided to go on a Sunday afternoon run in February. But unfortunately, he never returned home and his family was left to mourn his death due to two white vigilantes.

According to The New York Times, Arbery was running through a suburban neighborhood of ranch houses in a small coastal Georgia city when he passed a man standing in his front yard, who would eventually tell the cops that Mr. Arbery resembled a suspect in a string of break-ins.

According to a police report, the 64-year-old man, Gregory McMichael, retrieved his son, Travis McMichael, 34, and they grabbed their weapons — a .357 magnum revolver and a shotgun. The two white men hopped into a truck and started following Arbery, who is Black.

“Stop, stop,” they shouted at Arbery, “we want to talk to you.”

Not too long after they began chasing Arbery, there was a struggle over the shotgun and Arbery was shot at least twice and killed. Nobody has yet to be charged or arrested in association with the February 23 killing.

The president of the Brunswick chapter of the NAACP, Rev. John Davis Perry II, called the shooting “troubling.” Meanwhile, Arbery’s family and friends are concerned that the case, similar to the other senseless killings of Black people that have sparked protest around the country, might go unnoticed in the Deep South community due to the social-distancing restrictions amid the coronavirus pandemic.

“We can’t do anything because of this corona stuff,” explained Wanda Cooper, Arbery’s mother. “We thought about walking out where the shooting occurred, just doing a little march, but we can’t be out right now.”

Arbery was killed only three days before the anniversary of the 2012 killing of Trayvon Martin, who was chased and killed by a neighborhood vigilante, George Zimmerman, sparking the Black Lives Matter movement.

The New York Times secured documents that showed a prosecutor, who had Arbery’s case for a few weeks, told the cops that the pursuers had acted within the scope of Georgia’s citizen’s arrest statute, and that Travis McMichael, who held the shotgun, had acted in self-defense. The police report didn’t say whether Arbery was in possession of a weapon.

Gregory McMichael, a retired investigator in the district attorney’s office, couldn’t be reached for comment. Meanwhile, Travis McMichael, who operates a company that gives custom boat tours, refused to comment, citing the ongoing investigation.

The prosecutor who drafted the letter, George E. Barnhill recused himself from the case in April after Arbery’s family complained that he had a conflict of interest. A different prosecutor from another county is now leading the case and will determine whether it should be presented to a grand jury.

Meanwhile, activists and allies around Brunswick are ready to protest and bring attention to the case. A Facebook page has been started and a pressure campaign has been coordinated by emailing law enforcement officials and the local newspaper. Hashtags #IRunWithMaud and #JusticeForAhmaud have been created to spread the message, and T-shirts have been printed.

“There are a lot of people absolutely ready to protest,” said Jason Vaughn, a football coach at Brunswick High School who was over Mr. Arbery when he was an outside linebacker. “But because of social distancing and being safe, we have to watch what’s going on with the coronavirus.”

Arbery was killed in Satilla Shores, which is a quiet middle-class neighborhood about 15 minutes from downtown Brunswick and a short jog from Arbery’s neighborhood. He was wearing a white T-shirt, khaki shorts, Nike sneakers and a bandanna when he was killed. His family and friends believe that he was out exercising, however, others in the Satilla Shores neighborhood think differently.

On the day of the shooting, supposedly moments before the chase, a resident of Satilla Shores dialed 911, telling the dispatcher that a Black man in a white T-shirt was inside a house that was under construction and only partially closed in. “And he’s running right now,” the guy told the dispatcher. “There he goes right now!”

The former prosecutor, Barnhill, also brought up Arbery’s past record to the cops. Court documents show that he was convicted of shoplifting and of violating probation in 2018. Five years earlier, Arbery was also indicted on accusations that he took a handgun to a high school basketball game, according to The Brunswick News.

Despite suspicions, activists and family members stress that the incident didn’t warrant a chase by armed neighbors. “This incident was at the least a case of overly zealous citizens that wrongfully profiled the victim without cause,” Rev. Perry explained in an email. “These men felt justified in taking the law in their own hands.”

Arbery’s mother, Ms. Cooper, said she thinks the men judged her son by his skin color and she doesn’t believe he committed any crimes that day. She said if he did, then “he should have been handled by the police.” Ms. Cooper fought for prosecutor Barnhill to recuse himself from the case after she discovered that his son works in the Brunswick district attorney’s office, which had previously employed Gregory McMichael. Another Brunswick district attorney, Jackie Johnson, also recused herself quickly because Mr. McMichael had worked in her office.

Despite Barnhill distancing himself from the case, he wrote in his letter to the police that McMichael and his son had been legally carrying their weapons under Georgia law and because Arbery was a “burglary suspect,” they had “solid firsthand probable cause” to chase Arbery under the state’s citizen’s arrest law.

In another document, Mr. Barnhill said that video exists of Mr. Arbery “burglarizing a home immediately preceding the chase and confrontation.” In the letter to the cops, he lists a separate video of the shooting recorded by a third pursuer. Mr. Barnhill said this video, which has not been released to the public yet, shows Mr. Arbery attacking Travis McMichael after he and his father pulled up to him in their truck. Barnhill said the clip shows Arbery trying to take the shotgun from Travis McMichael’s hands and this action, Barnhill argued, warranted self-defense under Georgia law. Travis McMichael, Barnhill said, “was allowed to use deadly force to protect himself.”

Barnhill even went as far to say that Arbery’s “mental health records” and prior convictions “help explain his apparent aggressive nature and his possible thought pattern to attack an armed man.” The cops report is based almost solely on the responding officer’s interview with Gregory McMichael, who used to work for the police department from 1982 to 1989.

The case will now be taken up by Tom Durden, in the city of Hinesville, Georgia, who must decide whether the case should be presented to a grand jury for possible indictments. An Atlanta lawyer who formerly served as a U.S. attorney in Georgia, Michael J. Moore, reviewed Barnhill’s letter to the Glynn County Police Department along with the police report at the request of the Times and called Barnhill’s take “flawed.” In Moore’s view, the McMichaels appeared to be the aggressors.

“The law does not allow a group of people to form an armed posse and chase down an unarmed person who they believe might have possibly been the perpetrator of a past crime,” Moore said.

Meanwhile, Vaughn, the high school football coach, said that he and other activists were planning to put more pressure on authorities with an in-person action. According to him, they plan to drive to Durden’s office in Hinesville and mark spots on the sidewalk so that they remain several feet apart. Then they will enter the building, one by one, and question Durden’s office as to why the men who chased Arbery were not arrested.