Oil and chemical refinery plants cover the landscape, next to African American communities along the Mississippi River, in October 1998, south of Baton Rouge, Louisiana. | Source: Andrew Lichtenstein / Getty

Environmental pollution, partisanship and political theater are killing Black Americans. Not since the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 has legislation been so poised to shift the landscape of human rights within a generation. Today, watered-down environmental legislation blunts demand for decisive policy and participation in the name of crass compromise of Black people, rural, urban, or poor, served up for the appearance of progress.

Serious efforts at securing human dignity require an explicit and unshakable commitment to access for Black communities seeking breathable air, drinkable water and everyday infrastructure in the fight against climate change. Recently, the Biden-Harris administration presided over another call for Black people to wait. In a high-stakes contest, our government negotiated away the slimmest protections guaranteed in the National Environmental Policy Act to freeze the declining credit of our union. The president called the debt ceiling agreement “a compromise, which means no one got everything they want.” Those words belied an unspoken truth about the limit of meaningful engagement once it touches on restraint for markets, commerce and the lie of endless growth.

MORE: Understanding Environmental Racism And Its Effect On Black Americans

The Biden-Harris administration touted the debt ceiling compromise among its legislative accomplishments, chief among them being the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. At this point, it’s a rhetorical success for economic opportunity and energy infrastructure, whose truth depends on your vantage point. Aged, immigrant, poor, underserved, under-employed and unhoused people don’t have that privilege. The positive spin is doubly or triply toxic for Black, Brown and Indigenous populations whose baseline is lifetimes of scarcity, precarity and life on the margins. For example, $100 million in the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency grants for projects impacting environmental justice communities are meant to prioritize overburdened communities, yet the impact is questioned. Similarly, there have been plans for upwards of $12 million in federal funds for energy projects, which rely on technologies that communities made vulnerable have routinely rejected for failing to satisfy emissions, community health, safety, needs, or benefits.

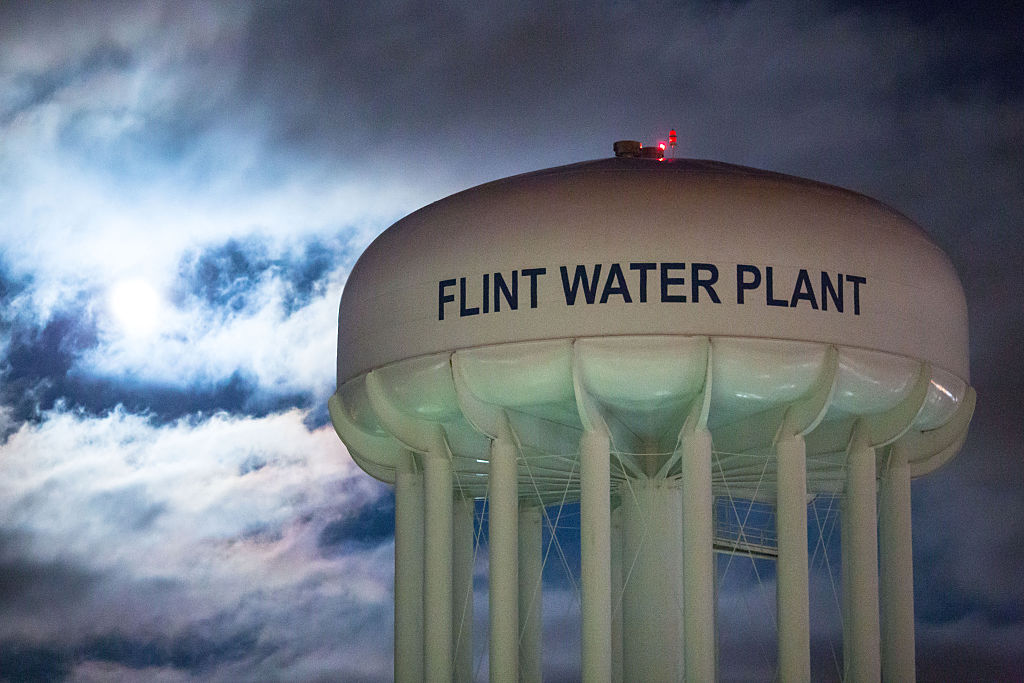

Source: Brett Carlsen / Getty

Well-meaning federal processes have yet to reach well-doing. The ways and means present predictable challenges, including short application periods, time-intensive applications, and little to no regional staff knowledge about engaging effectively with local needy groups. As a network of community groups, The Black Hive’s members see firsthand how bureaucracy is a priority where language, process, and staff are needed. Consequently, the smallest organizations serving communities are shut out of desperately needed opportunities.

In essential sectors such as solar energy, trade groups undermine federal guidance designed to support low-income communities to meet the call of generational power in every sense. The Low-Income Communities Bonus Credit program, included in the IRA, provided an additional 20% tax breaks for solar projects in minority low-income communities. Yet, challenges to this program risk misdirecting solar resources to old boys and their clubs, further exacerbating the inequities Black communities face.

The African diaspora will not benefit from equitable climate gains until the watchword of racial justice becomes standard, written explicitly into building codes, zoning regulations, and federal, state and municipal law.

The Biden-Harris administration still has time to adopt a more nimble, strategic, and relatable approach to ensure the equitable distribution of ecological justice resources to Black communities. Will it?

Georgia is a battleground contest for the Black vote. Atlanta is a city-wide hub of the Black community and the home of the fight to stop Cop City, where communities face an unfair energy burden that pits basic household budgets against basic service costs. Similarly, communities from Miami to Mobile, Michigan, and Oakland, among others, are looking to Justice 40, the initiative for federal redress of environmental injustices, to match its promise in impacted communities. We watch in horror as the benefits fall into old class bias and inequity patterns.

LaPlace, Louisiana on August 30, 2021, in the aftermath of Hurricane Ida. | Source: PATRICK T. FALLON / Getty

The debt compromise deepens systemic choices, guaranteeing lesser living conditions and poor health unless it is confronted. To complete the assignment, political leaders must prioritize environmentally just standards rather than knock down protections for Black people as a matter of human decency. No candidate should expect Black people to cast a ballot for them if we lack the proof in our own communities to justify it. As a people, we are not consigned to wrap our human dignity in self-destructive compromise. Our government has not worked for our votes, lives, or livelihoods for generations. And each time, we have been told to count to wait our turn.

Now is the time to show and prove. Black folk has always gifted proactive support to Democratic leadership. Future support must be tied to reciprocal assurances and an unequivocal fight against white supremacy, prejudice, and bias against our community, or else it’s just a game. Our human dignity is not a bargaining chip for the sake of deferred progress.

Tamara Toles O’Laughlin is a member of The Black Hive, the climate and environmental arm of the Movement for Black Lives. She is an international climate strategist and environmental advocate focused on people and the planet. She develops skill-building programs and creates multimedia campaigns to dismantle privilege and increase opportunities for vulnerable populations to access healthy air, clean energy, and a toxic-free economy at the local, regional, and national levels.

SEE ALSO:

EPA’s New Environmental Justice Office Pledges ‘Billions’ For ‘Those Who Need It The Most

Climate Justice For Black Futures: The Fight To Overcome The Legacy Of Environmental Racism